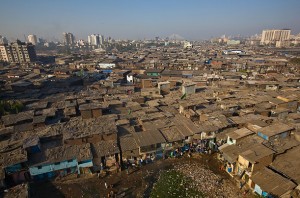

Dharavi is a slum in Mumbai that is characterized by living conditions that are sometimes not the most favorable ones. Its location in the city has changed in the past due to demolition in order to make way for new “legal” construction projects. However, Dharavi is a place that in itself is a mixture of different religions and cultures from all around India but whose population is extremely crowded into one sector due to large scale migration from rural areas during the latter part of the 1900’s. Furthermore, this combined with “inadequate supply of urban land and the lack of the creation of new urban centers resulted in extremely high density cities.” [2]These habitats of agglomerated living then amount for close interaction of these different people with quite similar goals and for a new kind of city that can be said to be “kinetic”. This elasticity of Dharavi to adapt is mostly based upon the fact of the high velocity with which construction is achieved and the ability to quickly dismount these dwellings due to the recyclability of the construction materials. Moreover, this kinetic behavior can also be seen as the personal adaptation that many of the inhabitants go through to live with people who at times in history they have been in conflict with.

The history that each inhabitant brings from their part of India contributes immensely to the development of the community. It is incredible that even though these groups are so different within themselves they still manage to organize themselves at the micro scale into their religious/cultural groups but come together at the macro scale to work in the informal job sectors and construct a better lives for themselves and the community. The human development of Dharavi is then quite advanced because if we consider a country with so much diversity in terms of languages, culture, and religion coming together in one neighborhood to live at peace then this is an achievement that many parts of the world are still trying to acquire. Consider the density of the population which is “an estimated 18,000 per acre. In this densely packed area you find twenty seven temples, eleven mosques, and six churches.” [1] It is no surprise that what surfaces for these inhabitants are not their less than desirable living conditions but the life stories and character of each individual.

Dharavi as Sharma states, “is the intermingling of the stories of its residents ordinary and extraordinary . Of their lives their histories and the history of the city of Mumbai.” [1]This allows them to create a developed neighborhood in terms of human interaction where acceptance has evolved to become a part of everyday life in order to create harmony and stand against the oppressions of those from the “formal” or “static” city. If we measured the level of human character development and perhaps not so much the material development then maybe we would not be so fast to connote these individuals with titles of criminals.

Discover Dharavi through its people:

1. http://www.tanya-n.com/?p=136

2. http://www.followtheboat.com/2010/06/06/the-dharavi-slums-of-mumbai-in-photographs/?nggpage=9

Bibliography

1. Sharma Kalpana, Rediscovering Dhavari: stories from Asia’s largest slum ( New Delhi ; New York : Penguin Books, 2000.), xvi-xxxviii.

2. Burdett, Richard, and Deyan Sudjic. “The Static and the Kinetic.” Living in the Endless City: The Urban Age Project by the London School of Economics and Deutsche Bank’s Alfred Herrhausen Society. London: Phaidon, 2011.

3. Berehulak Daniel, Mosaic of Poverty. Time Magazine, From Getty Images, http://www.time.com/time/photogallery/0,29307,1877000_1840436,00.html , Feb 2, 2013

//