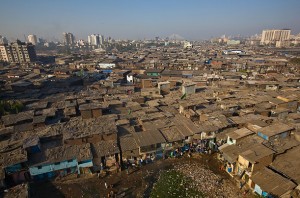

Dharavi, one of the biggest slum settlements, is worth $2 billion. With the booming population of today’s world, and the lack of land to build on, there is clearly a lot of attention to such settlements. David Harvey’s, The Right to the City, talks about the “most precious yet most neglected” human right to build and rebuild the city. (Harvey 35) So, say the government took over the land and moved the people from this settlement, what would that mean for the displaced people? The Indian Constitution states that they have a responsibility to “protect the lives and well-being of the whole population, irrespective of caste or class” – as almost any such document will say. (Harvey 35) Do they even deserve to be there in the first place? The Supreme Court believes that to go by such a ‘responsibility’ would be “rewarding pick pockets”… Harsh comment, but does the Supreme Court have a point? The title of Harvey’s article, Right to the City, can, by nature, be interpreted in many different ways from many different opinions. Who owns this right?

When talking about New York City, Harvey hypothesizes that there is going to be a “Financial Katrina”, where many of the low income neighborhoods, drowning in debt, will be cleared out. Will this then act as a blank-slate-like environment where those parts of the city could be planned again? Will there be planned developments to these parts of the city for the real-estate companies to make millions over? Thinking towards the sense of identity that is discussed in the excerpt from S, M, L, XL, what would be appropriate for the identity of such a place? Take a look at Dubai; a city which grew in just a decade or two, essentially the quintessential blank slate for an architect’s pen and paper. But what comes from the hundreds of developments and thousands of new homes that are being erected at an unimaginable rate. Dubai is essentially the airport city, “not only multiracial, also multicultural.” (Koolhaas 1252) One can even argue that with the collage of all sorts of projects, it lacks identity.

Look back to Dharavi, and compare it to Dubai in terms of identity. As Koolhaas describes, “The stronger identity .. the more it resists expansion, interpretation, renewal, contradiction.” (Koolhaas 1248) So while certain parts of New York City may undergo a kind of “Financial Katrina”, and may be more open ended to be able to absorb a variety of developments, what would happen to a place like Dharavi if the government did take over? With clearly a strong sense of identity, how much would this $2 billion land being drooled over but certain professions actually allow to take place? When talking about possibility of even more developments in certain parts of the world, Harvey argues that there have been no “coherent opposition to these developments in the twenty-first century.” (Harvey 39) Yes, there have, in my opinion based on these readings. Dharavi keeps itself from becoming the generic city as described in S, M, L, XL. While the right to the city, whether it’s yours or mine, is certainly there, at times there is a sense of history that has written the course of the natural development of the city.

Works Cited

Harvey, David. “New Left Review – David Harvey: The Right to the City.” New Left Review – David Harvey: The Right to the City. N.p., n.d. Web. 24 Feb. 2013.

Koolhaas, Rem, and Bruce Mau. S M L XL: OMA. S.l.: S.n., 1993. Print.