Author Archives: Andrew Illein

Microcredit across disciplines

The microcredit system, with all its success around the world, is an impressive solution to the lack of opportunity that keeps the poorest of the poor from climbing out of poverty. Using funds that are relatively small sums to encourage investment and the building of enterprise, with a system of trust for repayment, has the potential to eliminate poverty from society, as Professor Yunus describes[1].

When thinking ahead, what happens if/when the microcredit system becomes so successful that many of the poor households using the system are now off and running with their own enterprise or investments? One of the conditions of the microcredit system was that loans would not be used to purchase food or clothing, etc.

Another scenario that may have an interesting result is the use of microcredit across disciplines. Professor Yunus discusses how his healthcare ideas have used the system to help with one of the most demanding needs of life, and how it functions on the basis of trust when medical care must be given without payment being available up front. However, there are many other services and fields that provide necessities for those rising out of poverty. Architecture, for example, and the construction industry can provide the necessity of shelter, as well as arrangements for incorporating other family members or tenants into a living situation. Would microcredit also work for services such as architecture? Or would those services be considered enterprise for an investment?

Another idea is the concept of bartering; Professor Yunus’ interviewer discusses how Bangladesh is a homogenous culture of religion and people, with similar understandings and traditions and worldviews. If microcredit can work as a system that improves the culture and people group as a whole, instead of one person here and there, could bartering be used as a means of “income”? This could function on a larger scale than trading bread for a scarf for example. If a few people can wire electricity to your home, or provide construction labor for a new home, you could potentially repay them with another service they require. This is less applicable the more formal a society becomes, but may have potential to offset the lack of opportunities related to monetary income, and could potentially be organized in a record-keeping type manner, such as the microcredit loan system. Food for thought perhaps!

1. Dr Toh Han Chong, Interview with Professor Muhammad Yunus, SMA News, Volume 40 No. 12 December 2008.

The Brief and Business

In the “Spatial Agency: Other Ways of Doing Architecture” reading, many points and questions are raised regarding how architecture is practiced and how it can be thought of in a more “outside-the-box” way. One particularly direct inquiry raised in the text is on the topic of the brief. The brief is an integral part of architectural practice, and is described in the text as means of communication that “set out in varying degrees of detail the kind of accommodation required, the planning requirements, and often the overall cost” of a project that the client writing the brief wishes to pay the architect to accomplish.

Having worked in a very small firm, the experience from firm to firm is unquestionably different as to how these briefs are obtained, negotiated, and carried out. For a small firm however, much of the livelihood of the employer and employees is dependent upon the ability of the team to obtain a numerous and steady stream of projects, usually on the smaller scale, and complete them as efficiently as possible.

This leads to the issues that this text seems to overlook when discussing how architects can “have a greater impact” or “design the beyond.” While there are many aspects to architectural business and politics I do not grasp, the experience of the small firm, with perhaps one or two licensed architects and a few staff members, is largely dependent on the state of the economy and business from repeat clients. Without the backing of a political entity, high-profile donors, or a significant fundraising campaign, I question how these smaller firms can tackle the broader tasks the text is calling for. These are honest questions however, and I would be interested in expanding my knowledge in the aspect of the profession.

Crime – Division and Cohesion

Issues of crime in the global south have been documented to be both high and low in various poor communities. In the case of San Paulo, crime has played a role of division as well as cohesion. The divisive effects of crime, particularly violent crime, has caused a rift to be widened between the informal and the formal cities, leaving the “periphery” communities cut off from the formal, wealth-centered metropolis. This only makes sense, as violent crime increases, those who can afford to leave dangerous areas chose to do so. The result is a worsening crime rate inside the periphery – or so one would think.

The statistics given in “Worlds Set Apart” by Teresa Caldeira indicate that murders per 100,000 people have dramatically dropped in the past 10-15 years, down more than 75% from the year 2000. This is an indicator is progress being made in the poorer communities that must deal with crime and the lack of options to combat it. But what about crime that is not violent? “Crime,” referring to illegal activity in general, can take many forms, and some of which can have beneficial effects.

Caldeira talks about how the existence of violent crime has led to a discussion amongst the inhabitants of San Paulo that has manifested itself in a security-oriented living environment, with enclosures and walls being constructed and spaces becoming more privatized. In the periphery, this has led to a deep and vocalized movement of rap music. The idea of them vs. us and poor vs. rich and good vs. bad has become themes for lyrics that have helped build a culture and cohesive community of people going through the same hardships and dealing with the same issues through the almost spiritual bond of music.

Crime in the form of graffiti has also created a positive effect on the periphery residents. Caldeira notes how some San Paulo graffiti artists have becoming famous and are able to profit from their artwork, even though their trade is technically illegal and can be considered criminal.

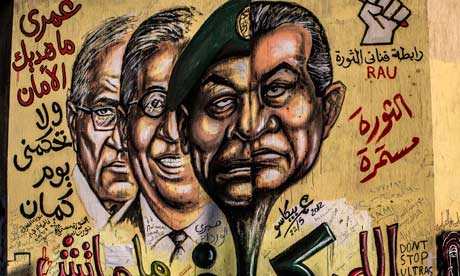

An interesting link to this cultural artwork is that of Cairo, Egypt’s young artists that have taken their people’s political protests and emotions and have conveyed them illegally on the public streets of downtown Cairo. As a form of protest that is there until the government can wash it away, the graffiti functions as both a recurring and present-day political speech, while also acting as a reminder of the past injustices the Egyptian people have memorialized as public art. In these ways, “crime” can be seen as serving a purpose in creating communities.

As a political reminder of the Egyptian Revolution of 2011, the people of Cairo have marked and added to this mural that shows the two-faced corruption of their government during that time.

Iconography as Generic

The ways that Rem Koolhaas describes the “generic city” in S,M,L,XL seem a bit vague and subjective – and yet, in a good sense, open to interpretation. When thinking about the ways that modern cities are becoming less individualistic, as the claim states, comparing the indicators of this process to the recent developments in Beijing reveal some different conditions that have perhaps slipped between the cracks.

As Anne-Marie Broudehoux lists in “Delirious Beijing: Euphoria and Despair in the Olympic Metropolis,” Beijing underwent a major overhaul as a result of having won the bid for hosting the Olympic games of 2008. The changes were explicitly designed to project Beijing as an iconic, memorable, unique, and powerful representation of China to the multitudes of visitors that would be faced with a first and perhaps only firsthand impression of China. Examples of the icons built include the National Theater designed by Paul Andreu, the National Stadium by Herzog and de Meuron, and the CCTV tower by Koolhaas. Iconic buildings designed by iconic architects tend to make for a more iconic city. But the argument presented by Koolhaas regarding the generic city conditions propose the question: is Beijing less “generic” for creating these icons, or do they simply work to turn Beijing into a modernized construct that can be created anywhere?

In theory, any city on earth, provided the cash was available, could hire the most well-known architects to design unique icons that make their city different or more recognizable. However, as reported by Broudehoux, the creation of the huge exclusive structures came at the expense of the urban fabric of Beijing, where the locals live and work and participate in their communities. By commercializing the skyline and newsfeed of Beijing with recognizable projects, the local, everyday, pure fabric of Beijing is destroyed. This is not to say that this fabric is what makes a city purely non-generic, but for those who are familiar with the city and its history and its communities, the new and alien constructs built by famous and wealthy people for more famous and wealthy people are not what they know as “Beijingian.” If the trajectory of this thinking continues, we might one day have a multitude of cities that are all iconic, all recognizable, and all fun to look at; and yet, that in itself will be generic, as the new language of extravagance and “look at me” syndrome becomes the ultimate goal for urban life.

Top-Down Towns

When reading about the industrial residential arrangements and comparing them to the PREVI-Lima project, the idea of bottom-up versus top-down communities came to mind. In both cases, the places where the local residents lived were “planned” in a top-down mentality, a contrast to the bottom-up concepts of emergence as discussed previously. And yet, within the top-down structure of urban organization lies the ability of the people of Lima to complete the housing project after the original planners were unable to do so. What makes the PREVI-Lima project so much more successful and humane than the industrial towns of the 19th century?

One initial point of interest in the top-down urban plan of these two sets of residential projects is that of the grand scheme. In both cases, housing was a necessity and a problem that needed to be solved. With the industrial towns, however, the housing was an afterthought. As described by Lewis Mumford in the book Slums and Urbanization, the plan started with the idea of profit and how to maximize gains from the prime placement of industries and railroads, and then an attempt followed to try and place as many dwellings for as little a price as could be engineered in the leftover space. Even in the less-than-livable towns this planning scheme created, there were still the basic elements of town planning: building structure and (some) utilities, doors and (some) windows, streets, etc. But it is the shirking of these efforts to the last priority that leaves them in such a lacking condition.

For the PREVI-Lima project, it’s as if all these factors that failed in the 19th century industrial towns were flipped and corrected, and in such a way that residents of the unfinished plan were able to understand and incorporate their own residential development into the local economy and community. The top-down order here was that of resident first, with profits and business coming from within the created community. As described in “The Experimental Housing Project (PREVI), Lima: The Making of a Neighbourhood,” “the PREVI experience demonstrates the importance of having a planning team with a comprehensive urban approach; since only with a complex and collective understanding of the urban phenomenon beyond the residential is it possible to create optimal strategies that enable its eventual users to continue the project’s development.” The top-down planning here felt it was important to include elements that keep the community alive and able to expand, as opposed to the strict, bare necessities of living provided by the industrial towns. These elements include the abilities for families to expand their houses, increase their income within the housing project, and the provision of purposeful pedestrian axis, traffic separation, and designated public spaces and plazas.

For top-down projects, as with any plan, those doing the planning and setting the wheels in motion have the greatest effect on the outcome of a project. With the PREVI-Lima project, its clear that with a comprehensive and purposeful design, a town can be created with enough momentum to even complete itself.

The Larger Ecosystem

The discussion about the concept of “emergence” seems so very broad and inclusive of so many topics and disciplines that distinguishing a solely architectural aspect is impossible. Emergence, with its concepts of connectedness and collectivity, will mean that architectural themes connected to the term emergence will be linked to other themes and topics. One such example is given in Stephen Johnson’s book “Emergence – The connected lives of ants, brains, cities and software,” where in the third chapter, he identifies the silk weavers of Florence, Italy as having remained in a single place throughout over a thousand years of history and being of a collective intelligence, which can be traced back to the guilds that originally established the communities of various trades in Florence. But the architectural and urban organization elements of Florence, although able to be categorized and interpreted under the concept of emergence and collectivity within the city of Florence, are linked to these silk merchants in a different way than the traditional situation of the silk weavers being occupants of the city’s architecture. They are instead the static element in the city, and the architecture is what has changed throughout the years.

On the second page of the Emergence in Architecture article, the author states that: “Emergence requires the recognition of buildings not as singular and fixed bodies, but as complex energy and material systems that have a life span, and exist as part of the environment of other buildings, and as an iteration of a long series that proceeds by evolutionary development towards an intelligent ecosystem.” Thinking about the slum of Dharavi in Mumbai, this is what occurs in the transient, kinetic cities that contain so many temporary structures. Each building or constructed shelter, outhouse, shop, market, home, etc. can be seen as a part of a development of the larger ecosystem and community of the kinetic city. The informal sector that these cities are a part of reminds of the lack of data able to be collected from these places, since many structures and land plots are not organized by a state or marked off with legal boundaries: they are a part of a larger, constantly-evolving system.

The above photo of Dharavi from the river demonstrates how the structures created in this larger system are somewhat indistinguishable from one another, and work together to create the spaces used for every part of an inhabitants life.

[Image from <http://www.mumbailocal.net/>]

Exploding Myths

When thinking about the attitudes of people living in slums, an assumption that seems easy to make is that the people forced to live in slum conditions will be bitter, depressed, and aggressive to get what they need. This would be linked to crime and violence that should be a regular occurrence in a place packed full of people with an attitude such as this. When compounded with religious tension and rivalry, it should only make matters worse. However, when reading about the slums in Mumbai, India, the opposite is true. Kalpana Sharma describes in his book Rediscovering Dharavi this assumption: “it is this deemed illegal status of informal settlements like Dharavi that makes people presume that they are breeding grounds for criminals and other ‘antisocial’ elements. It is also assumed that the spatial layout of such settlements, where people have no place to breathe and live literally on top of each other, exacerbated tensions – communal, class or caste….[yet] Dharavi explodes these myths.” Even though clashes have happened between the groups of Muslims and Hindus living together, Sharma demonstrates that the statistics are drastically low for this area.

A sense of community and dependence on others and the avoidance of conflict makes sense to cultivate in a slum environment, which benefits all parties involved. When trying to survive and provide for your family and yourself, fear of violence and crime is understandably something to avoid at all costs. In what may be seen as a benefit of this understanding is the link that the Mumbai slums have with the formal city. The connection between the “static city,” the formal, legal construct of Mumbai, and the “kinetic city,” the informal, always-changing slums, can be seen as desirable. Described by Rahul Mehrotra in Living in the Endless City, the attitude of being able to live together despite differences within the slums has become a conduit for the interconnectedness of the poorer class in the kinetic city living and inhabiting Mumbai alongside the static city.

The shared sense of community and survival of the kinetic city, with its drastically impermanent environment and the need to adapt to different neighbors and people groups is something that is worth studying more. In different places where kinetic-static city relationships exist, it would be interesting to observe the relationships between the communities and the individuals who share the same heritage and cultural backgrounds and locations.

In an interesting related post, this article notes the ways in which lower-income families in the Unites States have historically and consistently been more generous in terms of giving money, despite a lacking of it.

http://www.journalgazette.net/article/20120826/LOCAL10/308269954

Survival Mindset

The consensus from the published works on slums is that there must be something done to fix their current state and their future. When thinking about individuals in a slum, the attitude of survival is perhaps the factor that traps so many people in the life of poverty. When survival is the goal that must be met first, other goals of luxuries, recreation, comforts, and hobbies are put on the back burner. The economic benefits of money being spent on these other goals is something that can work to bring a community out of poverty, but clearly the requirements of earning enough to survive must be met first.

In John Beardsley’s article, “A Billion Slum Dwellers and Counting,” his concluding statement is that “…there may be no more pressing challenge to planetary health and security that the fate of slum dwellers. Helping to improve the quality of life in slums is not rocket science, yet every indication is that we are falling father and farther behind. The failures are probably more political than logistical or conceptual, and that might be the sorriest part of the whole story.” When thinking about overcoming the requirement of survival, it makes sense that necessities of life must be available and reliable. A link to the political failures mentioned in the article are the necessities such as clean water and sewage that now require either government involvement or massive private financial investment, both of which can be very politically bound.This contributes to the challenge facing planetary health as Beardsley notes, in that disease and pollution are the outcomes of the lack of necessities.

Because these necessities are not being met, the survival mentality continues, and is seen as a burden for the countries in which the slums are located. The challenge to global security, as Beardsley notes, can be a link to what Mike Davis calls “a realm of kickbacks, bribes, tribal loyalties, and ethnic exclusion” in his book Planet of Slums. Contributing to the survival mindset is that of pervasive threats, not just of disease or sickness, but of violence and aggression within the slums. Davis states that “Urban space is never free. A place on the pavement, the rental of a rickshaw, a day’s labor on a construction site, or a domestic’s reference to a new employer: all of these require patronage or membership in some closed network, often an ethnic militia or street gang.” The addition of a struggle to survive inside a violent network such as this is compounded with the struggle to survive with regards to life’s necessities, and further perpetuates the problem. Solutions involving breaking the survival mindset can certainly help in freeing the inhabitants of the slums to becoming more integrated with the formal society of their country.

http://offgridsurvival.com/survivalmindset/

Although geared more for wilderness survival, this link explains what your mind goes through in a survival mindset. The amount of stress and energy required to sustain this mindset for long periods of time can be what traps a person in their current state.