Professor Muhammad Yunus said in his interview in the SMA News that “if we can just provide the opportunity to poor people, there is no reason for poverty to remain a part of our societies” (Chong 5). While Professor Yunus was speaking in terms of microlending in this case, why is this particular concept not extended to architecture? He mentions that by bringing social businesses, which are “non-loss, non-dividend companies designed to address a social goal,” into the marketplace, we can improve the lives of the poor (Chong 4). Architecture firms could easily fall into this category, since they are still for-profit organizations for the most part, but have the ability to make drastic changes in peoples’ lives.

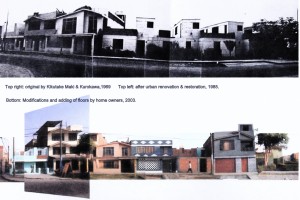

The work of Alejandro Aravena with his firm Elemental, for example provides housing to those who are desperately in need, yet it is still a for-profit organization. How can a firm balance their own need for profit with the desire to help others? A combination of micro lending and government funding may be a viable answer. When developing large scale projects like Iquique Housing in Chile, using micro lending in addition to government funding would increase the project budget, as well as provide a greater sense of ownership for those who will live in the houses. By taking out a loan in order to improve their house, they will immediately have a connection to it and care about its appearance, maintenance, etc. This will improve a home’s lifetime and, using Iquique as a model, the price of the home can increase exponentially in a short span of time (Aravena 32).

As we have seen throughout our investigations of architectural interventions in poor areas, participation is a key factor in a project’s success. Increased input from the community allows for final products that reflect the needs of the users, resulting in an increased interest in the project’s future. When people have put time, effort, and money into something, they are far more likely to care for it going forward. In this way, micro lending will drive those in impoverished areas to truly care about their surroundings in a new, positive way.

Providing those living in informal settlements with a stake in their homes and communities will provide them with an opportunity to get out of poverty. There is an opportunity for economic improvement through increasing property values as well as through the income from the shops that often take over the ground floor of homes in settlements such as Iquique and PREVI. Micro lending in conjunction with any available government funding is a clear and simple way to raise money for projects, increase community participation in the design and construction, as well as improve the lives of the poor going forward by giving them a home that over time can be profitable to them. It will allow architecture firms to remain for-profit companies while still aiding those in the most desperate need of their services.

Chong, Toh Han. “Interview with Professor Muhammad Yunus, Founder of Grameen Bank.” SMA News 40.12 (2008): 2-7

Aravena, Alejandro. Elemental: A Do Tank