Issues of crime in the global south have been documented to be both high and low in various poor communities. In the case of San Paulo, crime has played a role of division as well as cohesion. The divisive effects of crime, particularly violent crime, has caused a rift to be widened between the informal and the formal cities, leaving the “periphery” communities cut off from the formal, wealth-centered metropolis. This only makes sense, as violent crime increases, those who can afford to leave dangerous areas chose to do so. The result is a worsening crime rate inside the periphery – or so one would think.

The statistics given in “Worlds Set Apart” by Teresa Caldeira indicate that murders per 100,000 people have dramatically dropped in the past 10-15 years, down more than 75% from the year 2000. This is an indicator is progress being made in the poorer communities that must deal with crime and the lack of options to combat it. But what about crime that is not violent? “Crime,” referring to illegal activity in general, can take many forms, and some of which can have beneficial effects.

Caldeira talks about how the existence of violent crime has led to a discussion amongst the inhabitants of San Paulo that has manifested itself in a security-oriented living environment, with enclosures and walls being constructed and spaces becoming more privatized. In the periphery, this has led to a deep and vocalized movement of rap music. The idea of them vs. us and poor vs. rich and good vs. bad has become themes for lyrics that have helped build a culture and cohesive community of people going through the same hardships and dealing with the same issues through the almost spiritual bond of music.

Crime in the form of graffiti has also created a positive effect on the periphery residents. Caldeira notes how some San Paulo graffiti artists have becoming famous and are able to profit from their artwork, even though their trade is technically illegal and can be considered criminal.

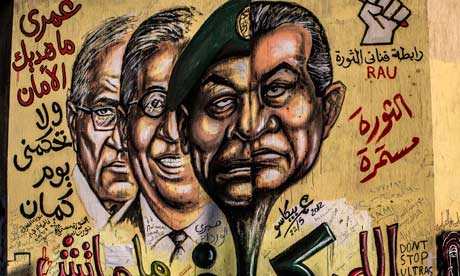

An interesting link to this cultural artwork is that of Cairo, Egypt’s young artists that have taken their people’s political protests and emotions and have conveyed them illegally on the public streets of downtown Cairo. As a form of protest that is there until the government can wash it away, the graffiti functions as both a recurring and present-day political speech, while also acting as a reminder of the past injustices the Egyptian people have memorialized as public art. In these ways, “crime” can be seen as serving a purpose in creating communities.

As a political reminder of the Egyptian Revolution of 2011, the people of Cairo have marked and added to this mural that shows the two-faced corruption of their government during that time.