Author Archives: Xue Yang

test

Social Investment

When dealing the crisis of poverty, most organizations and governments follow the prototype of social expanse on low-income families. However in the free market in capitalism system, it is hard and takes more effort for these “charities” to survive with more expanse than income. As Yunus mentioned in the interview “a market must be developed as a self-correcting system”, social conscience practices need work as a sustainable system that generate profit in the process of helping the poor and keep the organization survive independently. Both Grameen’s microcredit system and Elemental’s practices are based on the philosophy of creating wealth and helping the poor at the same time.

It is Yunus and Aravena’s trust on the ability and the contribution of local dwellers and the poor that makes their practices so successful. When talking about the inspiration of his belief in social enterprise, Yunus thinks that it the village women who “struggle daily for dignity and to create a good life for themselves and their families” (Dr Toh Han Chong, 5). The creativity and hardworking of the poor give passion for these social enterprise to invest and provide opportunity for poor people. Yunus believes that the reason for poverty is the lack of opportunity.

In order to help the poor, Grameen microcredit bank provides the low-income family with the opportunity to generate more income. And the regulating system with their outreach workers can make sure that the borrowers are using the loan for income generating purposes so that they will have ability to pay back to Grameen bank and have more money to support their families. Yunus extends this idea also to the Grameen Healthcare (GH) that they provide healthcare service first and the poor patients can pay for the service sometime in the future.

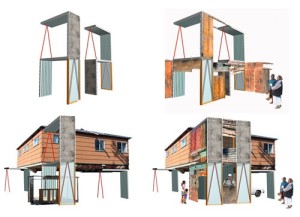

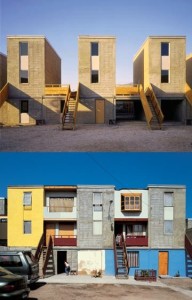

Aravena and Elemental uses similar philosophy in their architectural practices. The completion of buildings is not only architects’ job but also based on the dwellers themselves. Elemental provides highly designed architectural framework and leave the space for local dweller to add or change the building depending on their needs. Social enterprises like Elemental “empower local builders by giving them the knowledge that allows them to take these same innovations and apply them themselves” (Aravena, 35). This kind of practices saves the time and cost that are the most important in social housing projects. Each owner builds the second half the house and is responsible for “customizing the final solution” (Aravena, 35) in Elemental’s first practice in Iquique project in 2003. The value of houses increases because of the contribution of dwellers.

Also, the cooperation between institutions, enterprises and governments makes social investment easier in practice. “This unusual combination of academic excellence, corporate vision and entrepreneurship has been instrumental in enabling Elemental to expand its scope in the city” (Aravena, 32). Similar to Grameen, they create a health network that combine university and hospital center “hub” including a nursing college to serve for clients.

The sustainability should be the focus for more social organization and enterprises. Aravena and Yunus’s success give us good examples of social investment rather than only social expanse in social practices.

1. Dr Toh Han Chong, Interview with Professor Muhammad Yunus, SMA News, Volume 40 No. 12 December 2008.

2. Alejandro Aravena, ‘Elemental: A Do Tank”, Havard Design Magazine 21, Fall/Winter 2004/5.

Role of architects in informality

In the final section of the book Spatial Agency, the author discusses how spatial agents operate the concept inherent in these operations of the groups and practices.

It leads to the rethinking about the role of architects, especially in practices related to informal condition. Architecture can no longer be a beautified and technologized object and solve all problems alone. Especially when the book introduces spatial “appropriation”, architects need to face the fact of squatting and illegal self-building practices, in which new activities are created and embedded with long-term opportunities. The production and knowledge of clients and other forces is relatively more important compared to that in formal projects and should be included in the process of construction. The mark of architecture project’s completion has to be extended in order to consider the use of clients (informal recreate). However, the book also points out that today too often over-determined projects lead to inefficiency of space, as over-determined space is hard to transfer for other usage. While, some “slack” space, considered as wasteful and uneconomical, provides delight indeterminacy for everyday ordinary needs of transformation of space. Architects’ job is to set up the framework of a project with their professional knowledge and leave space for the inhabitation. In Teddy Cruz’s description about his practices in San Diego and Tijuana’s borderline, he invents a frame that cooperates with recycled materials and other human resource to “help dwellers optimize the threading of certain popular elements, such as pallet racks and recycled joists” as well as “acts as a formwork, allowing the user to experiment with different materials and finishes.” (Cruz, 35) Plus, the stair system benefited from this frame intervention accelerates the receiving of recycled houses from San Diego. The scale of architect’s part in this practice is relatively small, which is just simple transformable frame. However, the scale of this project is expanded incredibly big through the process of using these frames by residence with collective force. The indeterminacy is the basis for more future possibilities of the projects.

Based on the understanding of limitation of architecture and architects’ skill, we should agree with Marcuse’s view of using our skills in coalition with other groups to solve issues of capitalism in complex urban informality. In the book, author believes that “spatial agency is driven by the managing and administration of means such as labor, time and space.” Architects, as one important role with professional knowledge in the spatial agency, should take the initiation to collaborate with all other forces and spend time negotiating in order to make up the limitation in our knowledge and ability when facing such complex systems. When talking about “sharing knowledge”, the book says “architecture was not about supposedly neutral form, but about the collaboration with others in an attempt to make architecture and architectural tools more relevant to a broader section of society.” (Spatial agency, 78) In Teddy Cruz’s project in Tijuana, distribution of goods, ad-hoc services and the whole material recycling system connecting Tijuana and San Diego are all important aspects that architects need to negotiate and take into consideration in addition to the design.

1. Spatial Agency

2.Teddy Cruz, Tijuana Case Study

Mapping for Informal

Corner regards the agency of mapping as speculation, critique and invention. By introducing terms and techniques about his understanding of maps, Corner develops the idea that formal expression does not evolve quick enough to be relevant as long as the informal settlement starts getting more demand and rights.

Conventionally, neutrality is one of the conventional characteristics of “mapping”. However, the position, orientation, and differences of focus in maps all indicate certain socio-political statement. In Corner’s opinion, the abstractness of the map already brings in a subjective position of the mapmaker. “The application of judgment, subjectively constituted, is precisely what makes a map more a project than a ‘mere’ empirical description.”(Corner, 223)

The subjectivity of mapping leads to the re-thinking of the perspective in mapping. Banham, mentioned by Corner, suggests more attention on the problem that some mappings “adopt a somewhat naïve and insular, even elitist, position.”(Corner, 226)

“ The implications of a world derived more from cultural invention than from a pre-formed ‘nature’ have barely begun to be explored.” (Corner, 223) The mapping for the Watery Void project discovers the potential and pushes the design into a level with reconciled metropolitan and local scale. (Franco, 85)

As Corner mentions in the essay, he discusses “mapping as an active agent of cultural intervention.” Mapping is more like a creative activity that is not only a simple mirror of the existing reality, but also the design process for disclosing new reality. Comparing to “tracing”, mapping is a process of discovering and adding new elements in design.

Another comparison of concepts in Corner’s article is “mapping” and “planning”. He uses Harvey’s idea of “utopia of form” vs. “utopia of process” explaining the difference between “mapping” and “planning”. According to Corner’s description, mapping is definitely more useful and suitable for informal settlement, as mapping entails searching in the existing milieu instead of top-down imposed idealized formal project. Corner believes that various hidden forces underlie the workings of a place, which makes the reality more complex. Mapping of Sao Paulo’s infrastructure should not only be considered as a “technical and functional artifact”; but instead, the interrelationships and interactions between the rising middle class, the new demands coming together, as well as the interest of both central and peripheral residence cannot be ignored any more. One main concept of the Watery Void project is to use and serve for these interrelationships that form the complexity of mapping. Water, more than a nature resource in planning, becomes one main element bridging favelas with formal sector of the city.

James Corner: Agency of Mapping

Franco de Mello: Filling Voids

Competition and Boundary

As described by Daniela Fabricius in her article “Resisting Representation”, Rio de Janiero is a city filled with urban islands, favelas, which are geographically and culturally isolated. However the fact is that these urban islands are tied to the city with submerged structure. Favelas are everywhere in Rio. “The geography of marginality is identified with the people themselves, even if the place they inhabit is at the core of the city.”(3, Fabricius) The boundaries that separate favelas with formal sector are controlled by the competition between the formal and informal everyday.

Infrastructure, as the current flowing and connecting the city with favelas, is one main aspect in the competition. “Control over urban space is exercised not only through the ownership of property but also through the monopolization infrastructures.” (5, Fabricius) It’s interesting that the infrastructure in favelas is added after the informal settlement formed, as the reverse process of the inhabitation of formal cities with the grid and infrastructure installed first. It’s caused not only because favelas are all self-built, but also the formal infrastructural service provided by state and foreign companies is expansive and inconvenience for favela residence. In this situation, Gatos come out and dominate the competition. Illegal connections are made to legal sources of water and electricity in order to provide necessary infrastructure for favela residence that are unable to get formal utility. Gatos make the extension and connection within the system, at the same time, they provide possibility for representing the informal citizenship:

“citizenship is defined not only by an address but also by one’s utility bills, account numbers, and listing in a phone book, being connected by gatos creates vast populations that are by official standards undefined and unaccounted for, but in truth already intensely linked with the city.” (6, Fabricius)

The informal practice reveals its strength again in the competition on transportation. The routes of vans are organized based on favela residence’s demand. Also, “these vans provide the fastest and often the only way to reach the city centers.” (6, Fabricius) There seems no way for government regulation to help in the competition because of the illegality and flexibility of vans and the “van mafia”.

One the other hand, the government tries to take back control over the favelas through series of practices of “the favela pacification progress”. In the article “ Pacification and 24 Hour Surveillance in Rocinha”, author Carman introduces the competitive condition between government force and the drug gangs in favelas. The favelas become the battlefield of the invasion of these two forces. Rocinha becomes the “best watched place in the world” due to “cameras monitors watching nearly everything that goes on in public in Rocinha.” (Carman)

Three groups involving in these competitions are favela residence, government and illegal armed group. They are creating and defining the boundary of the favelas through the choice in the competitions.

1.Fabricius, Daniela, “Resisting Representation”

2.Carman, Andrew,”Pacification and 24 Hour Surveillance in Rocinha”, http://favelissues.com/2013/02/14/pacification-and-24-hour-surveillance-in-rocinha/

Inclusive and Exclusive City

There is no absolute division between formal and informal sectors within the city. Both Teresa Caldeira and Cynthia Smith believe that the informal settlement shouldn’t be homogenized and only represent poverty, violence, or slum. Instead, city itself is complex both socially and spatially. The heterogeneous informal sector has potential to contribute to city’s development when two sectors actually work together. It is the collaboration that brings life to the informal sector, which makes the informal sector become inclusive.

In the article “designing inclusive cities”, Smith provides several examples of collaboration across sectors to find solution to generate healthier and inclusive cities. Professionals, like architects and engineers, government and organizations all involve these successful projects of informal. The strategy of dealing with slums becomes benefitting for both sides instead of just clearing up the site and building formal sector on it. In solution “land sharing” in Bangkok, the architect makes private land shared with urban squatters, which creates commercial benefits for street front as well as legal tenure and housing for squatters. (Smith, 19) Similar practice that maximum the benefit for both sectors is “the Community Cooker” in Nairobi, Kenya. The whole process of the project solves the sanitation problems and saves money at the same time for the community. “Community members bring collected trash in exchange for use of the cooker, one hour or less to cook a meal, or twenty liters of hot water”. (Smith, 23) Dwellers’ life quality is improved with the effort of both community members and architects and other professionals.

The Community Cooker uses trash, collected by local youth for income, to power a neighborhood, cooking facility.

The income generating solution seems to be an efficient way to attract both sectors in practices of upgrading urban informal settlement. Smith mentioned merchants she met from the Kalarwe Market. They formed a micro-saving group that became like a market rather than a neighborhood. (Smith, 27) All segments of the city are brought together through these practices in order to form inclusive cities with the improvement of informal sector’s life.

On the other hand, Caldeira describes the exclusive situation of Sao Paulo in her article “Worlds set apart”. The high rate of violence becomes the inner force that makes the complex spatial separation of Sao Paulo. Physical dividers like fortified enclave and walls enlarge this gap between formal and informal sectors, with the addition of prejudice feeling formed within residents of the periphery themselves.

Smith, Cynthia E. Designing Inclusive Cities.

Caldeira, Teresa. Worlds Set Apart.

City Memory

“Instead of specific memories, the associations the Generic City mobilizes are general memories, memories of memories: if not all memories at the same time, then at least an abstract, token memory, a déjà vu that never ends, generic memory.”

Koolhaas S M L XL, 1257

Cities play an important role in every urban dweller’s memory. And urban architecture and landscape act as background or even identify our memory. The clear identity of a city strongly influences the memories that contribute to city’s image. Koolhaas uses the metaphor of lighthouse to describe this “identity”—“fixed, over determined: it can change its position or the pattern it emits only at the cost of destabilizing navigation” (Koolhaas, 1248). While after the spread of Neoliberalism and globalization, there are more and more cities from Global South countries tend to become “the Generic Cities”, where both urban landscape and people’s lifestyle move from difference towards similarity, which will finally lead to “memories of memories”(Koolhaas, 1257), the fading of city’s memory.

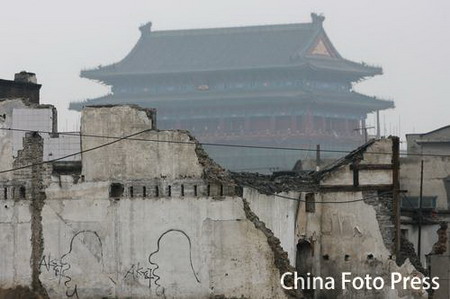

Beijing, as the city with imperial capital historical districts as well as new developing area, carries complex memories of more than 20 million local residences and migrant workers: old courtyard houses with gardens, vendors selling with verbal advertisement along old alleys, etc. However, these identical memories of Beijing are threatened by building booms towards to a Generic City. After Beijing won the bid for 2008 Olympic games, it’s interesting to see how these new monument building and avant-garde architecture are all from foreign architects whose practices locate in all parts of the world with the trend of Generic City. The conflict between identity city of Beijing and the newly built Metropolis filled with western avant-garde architecture corresponds with the one between general public and emerging economic elite in China. It is because of limited urban space and government’s ambition of rebranding city’s name in the world that Olympic facilities are built on the ashes of old neighborhood, and that eventually turning into “exclusive benefit of China’s emerging elite”. (Broudehoux, 91)

It’s ironic to see how deliriously Beijing is, sacrificing a cohesive and identical memory for most Beijingers, and reconstructing those “abstract token memory” with randomly placed “megalomaniacal architectural objects” that will only lead to a generic memory of a modern metropolis (Broudehoux, 101). However, we have to admit that people do simply enjoy their invention of this Generic City. The examples of protests that Broudehoux provides in the article are still limited to only very minority of people. Most Beijingers, in reality, even become millionaires, who we call “new elite”, by trading their authorities of identical memory with urgent and ambitious governors and developers in order to get the benefit like infrastructure of the new Generic City, which they consider as modern and better life.

Broudehoux, Anne-Marie. Delirious Beijing: Euphoria and Despair in the Olympic Metropolis

Koolhaas, Rem; Mau, Bruce. SMLXL. Generic City

http://news.sina.com.cn/c/p/2007-01-19/154612084451.shtml

The role of architects

When thinking about “architect”, it’s often linked to formal planning and projects with large amount of money invested. However, architects are also needed for those with low-income, especially after disasters. Architects take the responsibility to transform disaster into a chance for development. In Stohr’s article “100 years of humanitarian” he describes that the role of architects is in serving the needs of those who could least afford their services.

The Depression in America, two world wars and natural disasters all brought architects in 20th century to the point to rethink their role as architects when they pursuit the technology progress in “modern era”. Shelters and affordable housing became the focus of some architects at first half of twentieth century. However, with the widely spread of these proposals in post war era, more problems were raised around the world, which made these design more like an utopian idea, rather than policies with possibility of implementation.

The role of architects then needed to solve the division between “top down” policies and the “bottom up” emergence. Architects should work as mediation connecting this gap. Government and planers treat the poor as “million” instead of the problems and abilities for each individual when they start a large-scale project from a planner’s perspective. It leads to the fact that some of the “top down” projects cannot actually go down to the construction, like the problem of Prouve’s project that the prefabricated concrete, which successfully solved European housing crisis, was hardly promoted in developing country Ghana. On the other hand, architect Fathy realized this division between top decision and practices on site, and developed the housing project in New Gourna, Egypt with sustainable building techniques and local traditional material. Rather than taking the idea of “apostles of prefab and mess production” without understanding of the poverty of Egypt, Fathy’s proposal returned to the “bottom up” emergence system that individuals used for a long time without government’s planning. He believed that “each family will inevitably make it into a living work of art.” Stohr mentioned Fathy’s definition for the role architects as a “personal consultant yielding his or her training to the aspiration of the home owner and to the demands of local construction methods and material.” The role of architects should be like catalyst and lubricant that can make “top down” projects go through and arrive to individual practices. At the same time, emergence of “bottom up” housing should under the regulated and proposed from an overall perspective.

Education of an architect won’t end after graduation from an architecture school with second-and-third-hand knowledge. It’s usually more important for architects to learn those first hand knowledge from the local. The role of an architect should not limit in a utopian idea of his or her own knowledge, but more social responsibility.

Self-organizing Cities

When we try to understand architecture and the rules behind, it’s usually helpful to look at some universal rules applied on different aspects of the world. Emergent system, as a broad concept, provides an idea of forming and production in natural science as well as architecture. Under the explanation of “emergence”, cities start to be treated as models with organization and learning abilities, similar to brains and Web.

The human civic settlements usually form certain patterns when looking at them in helicopter view. And it’s possible to use inbuilt redundancy and multiple load paths to build models for complex city patterns and its behavior that are relatively stable in time scale of hundreds years. Reading “the pattern match” introduces three types of cities based on its emergence: traditional cities, imperial cities and organic cities. In organic cities, the patterns are shaped in time not only by physical structures with certain durability (like cathedrals and universities) but also community and business clusters with self-organizing ability. This ability can be understood as the inner force within clusters driven by information sharing (like Florentine silk weavers).

The self-organizing ability is another way of “learning”. The word “learning” is defined as “storing information and knowing where to find it”. So when a city learns, it recognizes and responds to changing patterns. At the same time, when it needs to respond the patterns, the system is able to alter and adjust itself without consciousness. It’s a new way to look at cities as a living organ that can respond to human activities instead of a static object any more. The learning process allows cities to record activities and form their own patterns like an emergent system in time.

Force of history keeps “lashing” the city pattern once it formed. While the balance between kinetic impact and static physical city structure creates a self-organizing structure and more over, develop the city. In reading “the Pattern Match”, the author raises the point that “a linear increase in energy can produce a nonlinear change in the system.” Cities can form a self-developing loop once energy or forces are added in. Here is a diagram showing how this loop works for European cities around 1000AD with the push of soil-based technology.

Similar energy increases in the society include later exploitation of fossil fuels and the information era that form self-organizing loop resulting with city development.

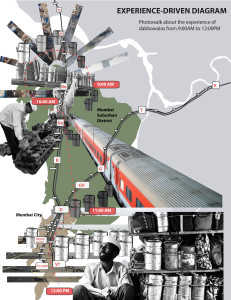

Mumbai, another example of this equilibrium of kinetic city and static city develop after the social and economic change in neoliberal era in late 20th century. The static part of Mumbai remains in its shape and creates new patterns with temporary housing and practices of kinetic city.

Michael Hensel , Achim Menges , Michael Weinstock. “Emergence in Architecture”

Stephen Johnson “Pattern Match”