Image by Leandro C.

Slums, favelas, gecekondu, and pueblos jovenes, all words with different pronunciations from different parts of the world but whose meaning is globalized and tied to the basic human necessity of shelter for the sake of protection. Within these informal settlements, the instinct to survive is materialized through every brick, concrete, and tin wall put up. At the global scale these flights for survival are made up of 70 million individuals leaving their mostly rural homes for reasons of education, war, accessibility, and money and traveling to cities to start a new life. As the book Shadow Cities demonstrates, “that’s around 1.4 million people a week, 200,000 a day, 8,000 an hour, every 130 minutes.” [1] As result, an act of survival that began with the individual has now transformed into one that indirectly affects the survival of the rest the world.

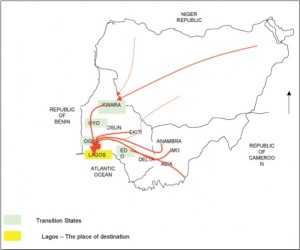

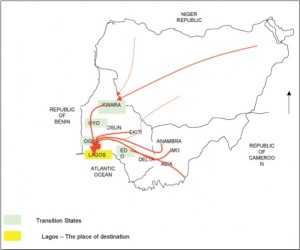

The different source migration regions into Lagos. [3]

From Lagos to Lima, the opportunities for jobs that cities offer throughout the world are more than likely the biggest attraction for these invaders to migrate. In the case of Lagos, “study revealed that socio-economic factors, such as better employment and educational opportunities, etc., were the main reasons for people to migrate to Lagos.” [3] However, many of these people cannot get a professional job within the confines of the legal city and for this reason are left to maneuver their way into an informal job into the squatter strata of society. As

Planet of Slums states, “the informal job sector constitutes about two fifths of the economically active population of the developing world. In Latin America the informal work force makes up 57 percent of the economy and constitutes four out of five new jobs.” [2] The informal working class is then one of the fastest growing economic classes on earth. Informal jobs allow many of these individuals who often have not had much education to sustain themselves within their own community practicing a particular task that most often they have a talent for. This work freedom is highly treasured by the inhabitants of these squatter communities and adding to it the freedom to choose where and how they build their homes gives these individuals a meaning to their materialistic unfortunate conditions.

We in the developed world have moved at least once or twice from a city to another but are restricted to the confines of what is legal. The individuals in these readings go through a same process of movement but do it within the context of the informal because it is the only thing available to them. The rent of an apartment for an individual from rural areas would simply be too great for his/her family to afford. They find pride then in the slow evolution of their housing compound and the help that their neighbors provide to continue their adaptation. The gradual construction allows then for memories to be associated with each aluminum sheet laid upon the roof or the laughter that was had with neighbors while trying to install a door. Construction for them has now gained a more human value or warmth that they begin to appreciate and hold on to strengthen their human instinct of survival.

These constructions at first sight seem to have no since of order but what is important to realize is that their order is one that although unorthodox to outsiders has a unity that is sometimes not seen by a mere observation. Each informal housing compound is adaption to the geography of the site, the shape of the formal city, and the cultural and basic needs of the inhabitants. The stacking space saving cubic homes in Rio would not be able to work in Lagos for the reason that one is in a mountainous coastal context while the other is in flat. Culture of course plays a lot into the construction of these housing units and it is seen in the materials chosen for construction. One would expect individuals coming from the country side in Kenya to utilize the same materials they used in their villages because it is what they have been using for thousands of years prior to their arrival. The materials in Latin America would be of concrete and bricks because of their cheap availability since colonial times.

Whether it is migration patterns, job opportunities, topography, materials, or even the act of building one’s own home every squatter community has something in common. The human need to survive and thrive gives purpose to these individuals while the freedom and human warmth that they find serves as a starting block for the new life they are trying to find.

Sources:

1. Robert Neuwirth, Shadow Cities(London : Routledge, 2004), xiii.

2. Mike Davis, Planet of Slums ( London ; New York : Verso, 2006), 176

3. P. Okuneye, K. Adebayo, B.T Opeolu, F.A Baddru, “ Rural-Urban Migration, Poverty and Sustainable Environment: The Case of Lagos, Nigeria” PRIPODE. http://pripode.cicred.org/spip.php?article79

For Further information take a look at these great articles and videos:

1. Migration Patterns: http://pripode.cicred.org/spip.php?article79

2. BBC Lagos Immigration: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8zdBRFWYizo

3. Life in Makoko district: http://www.economist.com/blogs/baobab/2012/07/nigeria%E2%80%99s-slums

4. Stories from slum residents in Kibera: http://www.economist.com/news/christmas/21568592-day-economic-life-africas-biggest-shanty-town-boomtown-slum

//

//

//

//