Any spatial challenge to the inefficiencies and inequities generated by the global domination of capital requires a principled political opposition and the social engagement of the most oppressed sectors of the working class. Spatial agency and networking are important tools to realize the goals of an anti-capitalist movement. While Lenin speculated on the subversion of bourgeois state power through the creation of a dual state, there is a more immediate potential for the generation of subversive spaces that have the ability to serve as a nucleus for further revolutionary action. Squatting settlements and slums are two examples where space functionally exists outside of state power.

Beyond some romantic revival of youthful 60s-inspired rebellion, these spaces can have explosive political consequences. The FARC-EP, though primarily based in Colombia’s countryside, operate urban networks of alternate governance in the informal neighborhoods of Colombia’s largest cities. This shadow government owes its efficacy to the informality of the space itself. While this example is certainly extreme and related to a specific political/geographic context, it demonstrates that informal conditions can generate highly sophisticated forms of spatial and social organization. Namely, the working class is capable of generating its own culture and spatial livelihood under even the worst circumstances.

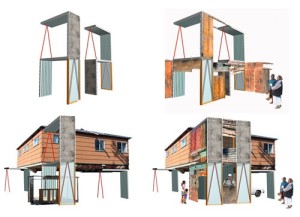

The next step in reorganizing space, drawing from Teddy Cruz’s methodology in Tijuana, is from the design point of view. The organization of the building project itself along a community-oriented mentality is capable of transforming how communities think about space. Teddy Cruz does not merely propose recycling San Diego’s capitalist refuse to build individual housing units; he contends that the act of social organization necessary for such an endeavor will reinvigorate a larger sense of collective power. Finally, he recognizes that the state will only recognize new settlements with infrastructural improvements only when these settlements exist as at least semi-permanent communities.

However, Cruz’s approach highlights the political roadblock that even the most well-intentioned projects encounter: how does one reconcile a principled critique of unjust systems while working to improve the lives of those most adversely affected by these systems? Cruz’s speculative design for housing in Tijuana has many positive, potentially liberating elements but does it not also ignore the glaring contradiction that Mexican labor is hyper-exploited by the Mexican and American bourgeoisies, literally bound by a wall to prevent any chance of social mobility and then forced to consume the leftovers of U.S. capitalism’s overproduction (in this case physical refuse and under-valued capital in the form of housing)? Architects must not only creatively work in contradictory, oppressive political climates but join movements to dismantle them.

Aquilino, Marie Jeannine. Beyond Shelter: Architecture and Human Dignity. New York, NY: Metropolis, 2010.

Awan, Nishat, Tatjana Schneider, and Jeremy Till. Spatial Agency: Other Ways of Doing Architecture. Abingdon, Oxon [England: Routledge, 2011.

Cruz, Teddy. Tijuana Case Study: Tactcis of Invasion: Manufactured Sites.