While Harvey aptly describes the city as a dumping ground for surplus value, allowing capital to expand relatively (as opposed to absolutely) in space, it is important to recognize that the right to the city speaks as much to the right to public ownership of the means of production as it speaks to public control over the means of distribution. The city is not merely hollow concrete buildings and its humbled inhabitants but a site of immaterial, creative, interpersonal and industrial labor. Whatever right to the city Harvey is searching for will have to be answered in terms of the right to publicly own the means of production as well.

The city, as a narrative, also offers the revolutionary question, “What happens now?” Harvey masterfully demonstrated how the success of Hausmannization was negated by the Paris Commune of 1871 and the “American dream”/suburbia could not contain the revolutionary explosion of the civil rights movement in the 60s. During the Modernist period of revolutionary upheaval from the Bolshevik revolution in 1917 to the demise of the socialist camp by 1991, imperialism and capitalist expansion was naively predicted to halt and lurch into fatal crisis once every conceivable area of the globe was parceled up by national monopoly capitalists in the West. While this prognosis seemed plausible in the heat of both World Wars, the Cold War demonstrated capitalism’s ability to survive crisis through the wanton destruction of surplus value and through the frenzied urbanization of the globe (Harvey 29).

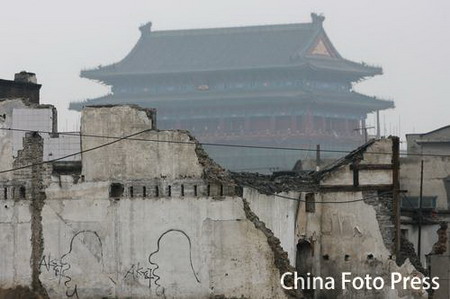

The question for revolutionaries and oppressed peoples in the 21st century is how to confront a system that seemingly can expand and revive itself infinitely. The answer is probably somewhat obvious: if capitalism expands infinitely through urbanization and the conscious destruction of surplus value, each instance of that relative expansion becomes a potential for rebellion. Of course there are no guarantees for success, as the Paris Commune was drowned in blood and the militancy of the American Civil Rights movement has led to a banal post-racial liberal excuse for equality. One could not conceive of the Paris Commune without Paris, nor the American Civil Rights movement without the march on Washington, but today’s conflicts with capital are generalized and universal. From the banlieus to the favelas to the slums, marginalization is meeting a common globalized enemy that cares little for tradition or national peculiarities. Following Rem Koolhaas’ logic of the Generic City expanding across the globe, the multitudes that are disenfranchised and forced to live informally or semi-legally are in some ways in an analogous position to the industrial proletariat of the 19th century. Broudehoux’s description of Olympics Beijing is indicative of this explosive social struggle, pointing out that corruption, growth and disenfranchisement represent the rule, not the exception (Broudehoux 100). The coming period of struggle and capitalist crisis is exciting from a revolutionary perspective because it is unprecedented in scope. The right to the city will have to be answered in the coming period because the 21st century city is the clearest example of capitalist exploitation. Whereas institutions such as the factory, church, or school previously articulated the roles in class struggle, today’s struggle can be understood on a larger, urban level.

Works Cited

Broudehoux, Anne-Marie. Delirious Beijing: Euphoria and Despair in the Olympic Metropolis.

Harvey, David. “New Left Review – David Harvey: The Right to the City.” New Left Review – David Harvey: The Right to the City. N.p., n.d. Web. 24 Feb. 2013.

Koolhaas, Rem, and Bruce Mau. S M L XL: OMA. S.l.: S.n., 1993.