In the past two hundred years, the world has undergone rapid, drastic changes that have altered how we live. With the Industrial Revolution came a focus on the factory rather than the human being. This meant that the living conditions of the workers fell far below previous standards, forcing up to twenty people to live in a single room (Mumford 21). Unsafe living conditions only continued with the continual growth of cities throughout the twentieth century. The question that architects must consider is how do we address these growing populations?

In One Hundred Years of Humanitarian Design, Kate Stohr discusses the importance of architects’ involvement in disaster relief and redevelopment projects. The question of whether architects should be involved in the processes at all seems to be one with a simple answer. Yes. If we can help others, why not? It is a matter of finding the correct method and design strategy for each location and situation. Each and every area in need of new or improved housing is unique, and there will most likely not be a single solution to such an immense and wide-reaching problem. However, there are a few factors that seem to create positive, lasting results no matter what the situation. Community involvement has proven to be one of the most effective tools when redesigning or redeveloping areas. For example, in Puerto Rico in 1949, a “government resettlement and land redistribution plan…[was started, in which] families were free to design and build their own homes using any method that made sense” (Stohr 43-44). This gave them the ability to create their own houses without being forced into accepting a design that does not relate to the context or their specific needs.

In contrast with community involvement is prefabricated design, something that in the post

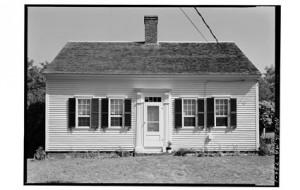

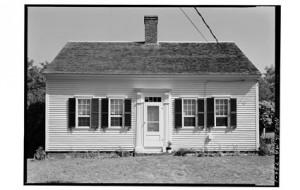

1: Levittown Cape Cod Kit of Parts

World War II era was one of the most useful tools that planners throughout the world had at their disposal. With both the influx of veterans returning from war as well as the massive amount of destruction throughout Europe and Japan, prefabricated, often Modernist structures were a logical building type to move away from the old, pre-war state of mind, and into a new era. Levittowns

2: Levittown Cape Cod Constructed

sprouted up all over the world, from Long Island, NY to Iran, Venezuela, Nigeria, France, and Israel (Stohr 46). Pre fabricated housing such as Levittowns have not proved as useful for disaster relief situations, because often, even if the structure is a simple tent, it may not arrive on site early enough to make an immediate impact, nor will it provide much more than an extremely temporary solution to a permanent problem.

An additional necessity for a successful future for a project is ownership. When squatters do not own their homes, they often lose the desire to rebuild or revitalize the existing structure since they live in constant fear of losing what they have.

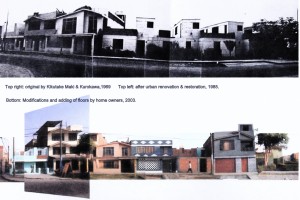

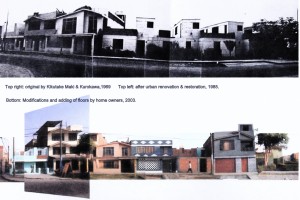

3: 1978 to 2003 Adaptation of PREVI

This was addressed in PREVI, in Lima, Peru, because the new residents owned the homes and were encouraged to add to them as time and money allowed. In fact, it was part of the project brief itself that the structures be easily added to. This meant that they were invested in the future of their homes, and were free to make them into anything they wanted to. The ability to adapt each home to the occupants specific needs creates a dynamic city with a variety of aesthetics that are each uniquely personal. In this way, despite the standardized designs that each architect involved in PREVI created, each block no longer appears monotonous, but rather incredibly active, each house with its own character.

With the rise of NGO’s and aid organizations, architects have no excuse not to help those in need of well designed, sustainable homes. We have the knowledge and skills to improve the living conditions of the immense percentage of our planet that currently lives in slums, yet somehow nothing is done about it. Stohr’s article proves that between architects’ knowledge of building systems and planning, and the input of those in need of housing, relief and renewal projects can most certainly be successful.

1: http://starcraftcustombuilders.com/Architectural.Styles.Postwar.htm

2:http://invinciblearmor.blogspot.com/2010/08/cape-cod-original-levittown-house.html