Reading about the static and kinetic components of a city is a fascinating idea that creates a multitude of opportunities. The relationship between the two means for unique moments of interventions in the interstitial space between the two city identities. More opportunities come up when one considers the temporary characteristic of the kinetic city. It constantly modifies itself, and therefore is naturally created by materials with a temporary characteristic; as opposed to the more permanent, and common, building blocks of the static city. (Burdett 108) I find it particularly interesting when the reading begins to subtly label the kinetic city as having more of a ‘cultural memory’ as opposed to the static city which is, once again, subtly labeled as being more ‘object-centric (devoid of life)’. (Burdett 111) Furthermore, the issue of boundary, something that was also brought up last week when referring to the boundary of the formal and the informal market, an area Urban Think Thank referred to as Urban Acupuncture, is brought up again this week when discussing the boundary between the static and the kinetic city. An example given in the reading is the porch-like structure that is built by the PWD and attached to a building to protect the people from monsoons. What made me curious about this event was that the already-curious-boundary between the kinetic and static all of a sudden become even more blurred, in a symbolic sense, than they already are as the kinetic city clearly expands itself into the static, even if it’s momentarily. It raises quite a few questions, such as how the people living in the formal and static city respond to the informal and the formal city. While many of these readings are written from the point of view of the residents of the slums and their way of life, it might be interesting to see how the formal population sees it. How would they feel about a temporary structure that is attached to their building?

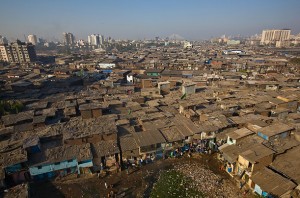

Looking at Rediscovering Dharavi, a small portion of the reading discusses a “a time when it was seriously argued that efforts should not be made to ease the lives of the urban poo by providing them basic urban services or house, because then many more of their kin would rush to the city.” (Sharma 37) Yes, argued that efforts should not be made. Recognizing that the government, or the people in charge of making such decisions, is part of the formal market and the static city, it is an interesting notion that such a train of thought actually existed at one point. Of course, by the 1980s, this kind of thought was scrapped and a more humane approach towards the topic was achieved. In fact, it is hard to label the government as being inhumane by thinking in that way because, “a place like Dharavi poses several difficult challenges for the government.” (Sharma 37) Part of the book discusses a what-if scenario: what if the government had anticipated the fast growth of Mumbai, and invested in low-cost, low-income housing for migrant workers? “Some of the present crisis that the city faces would have been averted.” (Sharma 35) While there exists a notion of nallah, or the diving line between settlements in Dharavi, one wonders the extent of the boundary between the static and the kinetic, the equivalent of the nallah, on a bigger scale. (Sharma 10) As mentioned earlier in this entry, this idea of the bigger scale nallah, the interstitial space, is what makes the urbanity of Mumbai so interesting.

One cannot deny that the “slum is not a chaotic collection of structures; it is a dynamic collection of individuals.” (Sharma 34) And these individuals, with years of trial and error, have figured out a way to live with each other, to tolerate each other. Not only is this true for the nallah boundary within the slums, but also the greater, more curious boundary between the static and the kinetic. Their coexistence with each other, their sense of being intertwined as a machine which works together, is made apparent with the concept of Dabbawalas. These “tiffin suppliers”, deliver food to thousands of workers across the city. (Percot 1) These informal employees visit the homes of dozens of employees, pick up the food that was prepared for them, and deliver it right to their workplaces. A job that is clearly in the informal sector, but very much thrives on the formal sector. In fact, it has become such a popular industry that it is “elevated to the status of model of Mumbai entrepreneurship.” (Percot 1) The idea of the Dabbawalas is very unique. While many will wonder why the worker won’t just bring his own food to the work place, it is apparent that the density of Mumbai makes it extremely difficult to carry one’s food to work at the peak of rush hour. The idea of the Dabbawala is pure entrepreneurship. Not only does it take a situation which might seem unfortunate for many and turn it into a job that satisfies both sides of the business, but it is a clear demonstration of the intertwined existing of the two economies, formal and informal, and the two cities, static and kinetic.

Works Cited

Burdett, Richard, and Deyan Sudjic. Living in the Endless City: The Urban Age Project by the London School of Economics and Deutsche Bank’s Alfred Herrhausen Society. London: Phaidon, 2011. Print.

Percot, Marie. “Dabbawalas, Tiffin Carriers of Mumbai: Answering a Need for Specific Catering.” (n.d.): 1-10. Web. <http://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/docs/00/03/54/97/PDF/DABBA.pdf>.

Sharma, Kalpana. Rediscovering Dharavi: Stories from Asia’s Largest Slum. New Delhi: Penguin, 2000. Print.