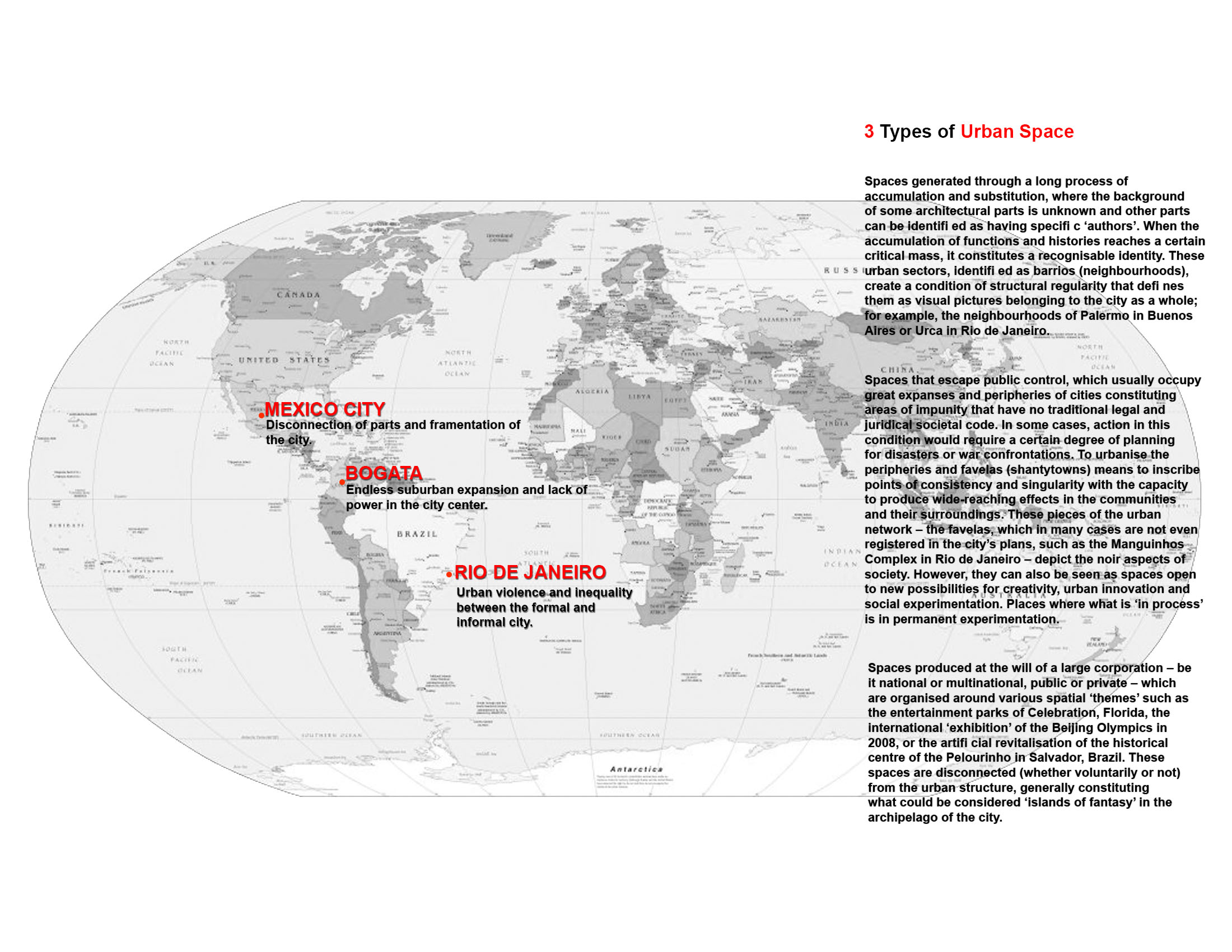

Urban Acupuncture Reiterated

It’s really exciting to regularly see connections between the different readings that are done throughout this class. Particularly an overlap of ideas and thoughts regarding issues of informal and formal cities. One thing I have been particularly interested in since the beginning of our discussions has been what Urban Think Tank call, “Urban Acupuncture”. This term has come up a few times under this label, and has come up multiple times as a concept. It refers to the connection between the formal and the informal parts of the city. According to the Designing Inclusive Cities, the fact of the matter is that “We are not able to make services available as quickly as the growth.” (Smith 13) Informal cities exist. And they are often growing much faster than their formal counterparts. According to Cynthia Smith, Urban Think Tank, and many other thinkers, one of the best solutions is “hybrid solutions that bridge the formal and informal city.” (Smith 13) It’s often the case that entrepreneurship that has formed through the opportunities in the informal city become integrated with the formal city; showing that the two co-exist. A discussion that came up during class last week was how the architect contributes to the informal city – or if they do at all. At the end of this brief discussion, we began to realize that architects, of course, contribute to the formal city, which by it’s characteristics creates opportunities for the informal city to latch on. The motorbike taxis in Dakar are quintessential to the blurred line between the formal and the informal. These taxis are a form of cheap transport, and offer services to all types of people. Instead of getting rid of these ‘illegal’ services, the government decided to register them and provide signs to make them more distinguishable. This is the perfect example of the Urban Acupuncture, or the bridge between the formal and the informal.

According to Worlds Set Apart, Sao Paulo is a “city is made not only of opposed social and spatial worlds but also of clear distances between them.” (Caldeira 168) This creates an immediate donut-like diagram where the center is the ‘formal’ city made up of middle and upper class, and the surrounding area of the donut is the ‘informal’ city where the lower class are spreading to the periphery. A solution to this was often thought to be to expand the infrastructure of the city to the periphery and provide basic living necessities to the residents of the periphery. Such actions could have major impacts on the survival rate of new born children, lower crime rates, less drug use, less diseases, etc. Sao Paulo and the favelas is a great example of this. Jorge Mario Jaurequi is an architect who has had multiple Favela-Barrio projects which are designs to create a better sense of connection between the formal/informal and improve living standards. His projects, often simple interventions, are an example of what a big impact small scale changes can have. The connection between the formal and the informal is crucial, and it is almost a necessity that the two exist together. (Jaurequi 60) He values the importance of being able to recognize the ‘other’ – the 90% of the world’s population which is often ignored during design by design professionals. (Smith) Jaurequi encourages us to recognize the ‘other’ in order to insert more humanitarian designs into our lives.

Works Cited

Caldeira, Teresa. “Worlds Set Apart.” LSE Cities. N.p., n.d. Web. 03 Mar. 2013.

Jaurequi, Jorge M. “Articulating The Broken City and Society.” Architectural Design 81.3 (n.d.): 58-63. Print.

Smith, Cynthia E. Design with the Other 90%: Cities. New York: Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum, 2011. Print.

The Informal as Architecture without the Architect

The informal urban is thought to be an ad-hoc eternally self-evolving and changing entity. The lack of consciously recognized order or method is what makes the informal informal. But to say that the informal is lacking in design is likely not doing the order that exists within the informal justice. Example after example has shown that the informal has a method to its madness, a controlled chaos in a sense. The informal city has a grain all to its own. That grain can be called the design of the informal. But that asks whether design can exist without the designer.

The designer creates and and invents. Designers vary in their methods and products. One type of designer or architect creates based on the inevitable set of contextual conditions that face the architect. The generic constraints are site boundaries, topography, environmental, programmatic budget, political ect. All of these conditions must be righteously integrated into the design and the designer must be aware of all of the conditions. Thus the designer creates a comprehensive and effective design.

The informal city does not have the designer and the design rigor. But how then does the informal city creates it’s grain? How does it develop its “design”? The design is made naturally. The same way that the designer must think about the constraints the informal city must think about its constraints. When an informal city is built in the hillside and every structure sits along the hillside almost create topographical lines of the geography constraints that are being adhered to. The lack of a budget, this time meaning a lack of funds instead of a “money is not object attitude” causes the informal city to be the cheapest it can be. Thus the informal city creates its own typology and thus creates its own design. And this is done without the help of the designer.

But is it still designer even though the designer dose not exist? To answer this question the product of the design has to be thought about more. The final product is not where the design ends. the final product is really where the design begins. When the user of the design interact with the designed object and activates it it inherently changes. The designers’ control has been abdicated. Now the product is used as the user see fit.The object is not used as the designer intended. This is the point when the designed object is now the used object.

The informal city is a used object and thus is reconfigured ever evolving and ever changing. So once again one can claim that the informal city is the designed city even though there is no designer. Still begs though what the implication of this question is. It is to ask if the informal, the design liberated from the designer,can be judged in the same way that the designer based design is. Really it is asking can something be learned form the informal and thus can this learning experience give the informal power?

Inclusive and Exclusive City

There is no absolute division between formal and informal sectors within the city. Both Teresa Caldeira and Cynthia Smith believe that the informal settlement shouldn’t be homogenized and only represent poverty, violence, or slum. Instead, city itself is complex both socially and spatially. The heterogeneous informal sector has potential to contribute to city’s development when two sectors actually work together. It is the collaboration that brings life to the informal sector, which makes the informal sector become inclusive.

In the article “designing inclusive cities”, Smith provides several examples of collaboration across sectors to find solution to generate healthier and inclusive cities. Professionals, like architects and engineers, government and organizations all involve these successful projects of informal. The strategy of dealing with slums becomes benefitting for both sides instead of just clearing up the site and building formal sector on it. In solution “land sharing” in Bangkok, the architect makes private land shared with urban squatters, which creates commercial benefits for street front as well as legal tenure and housing for squatters. (Smith, 19) Similar practice that maximum the benefit for both sectors is “the Community Cooker” in Nairobi, Kenya. The whole process of the project solves the sanitation problems and saves money at the same time for the community. “Community members bring collected trash in exchange for use of the cooker, one hour or less to cook a meal, or twenty liters of hot water”. (Smith, 23) Dwellers’ life quality is improved with the effort of both community members and architects and other professionals.

The Community Cooker uses trash, collected by local youth for income, to power a neighborhood, cooking facility.

The income generating solution seems to be an efficient way to attract both sectors in practices of upgrading urban informal settlement. Smith mentioned merchants she met from the Kalarwe Market. They formed a micro-saving group that became like a market rather than a neighborhood. (Smith, 27) All segments of the city are brought together through these practices in order to form inclusive cities with the improvement of informal sector’s life.

On the other hand, Caldeira describes the exclusive situation of Sao Paulo in her article “Worlds set apart”. The high rate of violence becomes the inner force that makes the complex spatial separation of Sao Paulo. Physical dividers like fortified enclave and walls enlarge this gap between formal and informal sectors, with the addition of prejudice feeling formed within residents of the periphery themselves.

Smith, Cynthia E. Designing Inclusive Cities.

Caldeira, Teresa. Worlds Set Apart.

Helping the other “Half”

Informal settlements around the world have begun to catch the attention of not only philanthropists but also of design driven professions such as architects, engineers, and artist of all types have found potential in the rejuvenation of these locations. Architecture firms such as Metropolis Projetos Urbanos have added into their design purpose the rejuvenation of spaces deemed lost to informality by the citizens of the city. Artist such as JR have also created projects utilizing the buildings in the favelas of Rio as a canvas to portray the stories held within the boundaries of the neighborhood.

In the past designers have exclusively focused on designing for a very small margin of the world population that can provide money for planned designs. As Cynthia Smith states, “ Professional designers have traditionally focused on the 10 % of the world’s population that can afford their goods and services”.[1] Currently, there seems to be a trend to incorporate newly commercialized forms of technology in order to incorporate sectors of society that in the past have been previously ignored. In part recent advances in technology such as Google earth, YouTube, and the internet in general have allowed individuals from developed countries to observe the way of life of individuals who are not as fortunate as they are. This has gathered the attention of designers who want to place power in their own hands and solve as Smith states, “solve the world’s most critical problems”. [1]

The individuality of each informal settlement as a result of the structural and formal adaptations it has undergone to adjust to the context of its site must be considered when designs are being created. Firms such as Proyecto Arqui5 identified the uniqueness of the La Vega community in Caracas. As a result, the stair design that incorporated water sewage systems throughout the settlement was designed with not only with the sites context in mind but also the needs of the people who inhabit the spaces as well. Other organizations like Surat City have utilized the internet to aid in the development among the poor over the effects of global warming in the community. Creating a solution is important but making sure the solution works with existing factors such as topography, climate, geography, displaced individuals, and famine is crucial because this can actually help the neighborhood evolve beyond its present situation.

Creating solutions for the neighborhood must go along with bridging the divide that exists in many cases with the formal city. Through projects of infrastructure, construction of social, security, medical, and health facilities one can create situations where the informal has been incorporated into the rest of the city and instigated a feeling of self-worth within the inhabitants of these localities. As Jorge Mario Jauregui writes in his article, “The aim is to articulate the divided city and society by providing greater accessibility, investments in infrastructure, new public social facilities, and environmental revitalization, connecting the formal and the informal parts of the city” [2].

To employ these policies a step by step process must be undertaken that truly involves the community in the actions that will take place in the community. Site visits have to be included in order for the architect, artist, designer, etc. to be able to have a better understanding of the surroundings she/he will be designing for. One thing is to assume the problems of the community but another is to actually talk with members or representatives who actually know the issue the community has to deal with on a daily basis. Researching the history of the community where each person comes from and why things are the way they are critical in creating a better future for the communities.

The advancements in technology have created a more connected world that gives the possibility to understand each other’s problems. As a result this has created interest in various fields in regards to helping those in less than ideal living situations. However, as help is brought to these people the different steps must be considered because they lead to solutions that can really go for the root problems not just the superficial ones and in effect have a longer lasting imprint in the lives of those we want to help.

1. Cynthia E. Smith, Designing Inclusive Cities, ( New York : Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum, 2011)p. 13- 29

2. Jorge Mario Jauregui, “Articulating The Broken City and Society”, ( Architectural Design , 18 April 2011), p. 58-63

//

Crime – Division and Cohesion

Issues of crime in the global south have been documented to be both high and low in various poor communities. In the case of San Paulo, crime has played a role of division as well as cohesion. The divisive effects of crime, particularly violent crime, has caused a rift to be widened between the informal and the formal cities, leaving the “periphery” communities cut off from the formal, wealth-centered metropolis. This only makes sense, as violent crime increases, those who can afford to leave dangerous areas chose to do so. The result is a worsening crime rate inside the periphery – or so one would think.

The statistics given in “Worlds Set Apart” by Teresa Caldeira indicate that murders per 100,000 people have dramatically dropped in the past 10-15 years, down more than 75% from the year 2000. This is an indicator is progress being made in the poorer communities that must deal with crime and the lack of options to combat it. But what about crime that is not violent? “Crime,” referring to illegal activity in general, can take many forms, and some of which can have beneficial effects.

Caldeira talks about how the existence of violent crime has led to a discussion amongst the inhabitants of San Paulo that has manifested itself in a security-oriented living environment, with enclosures and walls being constructed and spaces becoming more privatized. In the periphery, this has led to a deep and vocalized movement of rap music. The idea of them vs. us and poor vs. rich and good vs. bad has become themes for lyrics that have helped build a culture and cohesive community of people going through the same hardships and dealing with the same issues through the almost spiritual bond of music.

Crime in the form of graffiti has also created a positive effect on the periphery residents. Caldeira notes how some San Paulo graffiti artists have becoming famous and are able to profit from their artwork, even though their trade is technically illegal and can be considered criminal.

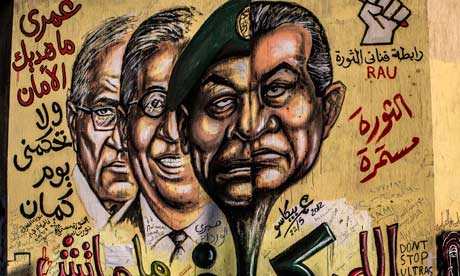

An interesting link to this cultural artwork is that of Cairo, Egypt’s young artists that have taken their people’s political protests and emotions and have conveyed them illegally on the public streets of downtown Cairo. As a form of protest that is there until the government can wash it away, the graffiti functions as both a recurring and present-day political speech, while also acting as a reminder of the past injustices the Egyptian people have memorialized as public art. In these ways, “crime” can be seen as serving a purpose in creating communities.

As a political reminder of the Egyptian Revolution of 2011, the people of Cairo have marked and added to this mural that shows the two-faced corruption of their government during that time.

Recognition, Intervention and Respect: Engaging the Informal

Although this is seemingly obvious, the first step in transforming informal communities is recognizing the scope and permanence of these urban phenomena in the first place. The spatially jarring, almost fantastical images of favelas engulfing the boundaries of gated communities in Brazil points to this issue dramatically. Even though informality in urbanism is expanding rapidly and affecting societies around the globe, economic/social/political marginalization remains a major hindrance to the advancement of social justice in these communities.

The paradox of aid and development lies in the fact that informal communities physically need to be transformed in order to promote the health and wellbeing of residents while simultaneously understanding that these communities are inhabited by individuals who have agency and their own conceptions of space, dignity and development. Top-down approaches are not necessarily good or bad but require a heightened awareness of conditions on the ground in order to be effective. While The City of God dramatized the difficulties of growing up in informal settlements in Brazil, it also gave the impression that the culture of gang violence was so pervasive that it dominated life itself. While hard-hitting and based in reality, the film does not take into account the richness of life beyond gang violence. Ironically, the film’s main character comes of age by straddling the boundaries of the formal and informal, fulfilling his lifelong dream of becoming a photographer through strange twists of fate that result from his peripheral relationship to the gang war. The film culminates in a detached journalistic account of the violence, departing from the first person narrative that characterized the beginning of the film.

Teresa Caldeira identifies the film’s main limitation as giving the false impression that the experience of life in the favela was universally characterized by gang life. She counters this approach by celebrating grassroots forms of culture such as hip hop and street art that articulate an entirely different conception of marginalization and class/racial division (Caldeira 174). Her approach recognizes the cries of protest coming directly from the favela as a more genuine form of cultural expression and identity.

Where does the role of the architect and urban planner fit into these questions of culture and identity? Successful interventions must be critical of condescending grand narrative assumptions about daily life in informality and avoid generalizations while recognizing the need to improve material conditions on the ground (Jáuregui 60). This mentality suggests that the person behind the intervention have a personal connection to the community in question, similar perhaps to Robert Neuwirth’s project of embedding himself in informal communities. Even a project as simple as a community well or latrine involves a complex series of questions concerning site, access, existing conditions and the community’s relationship to land itself. Attempts at blanket solutions, such as giving land titles to entire communities of squatters, demonstrate that there are limitations to approaches that do not correctly assess conditions on the ground.

Jáuregui, Jorge Mario. Articulating the Broken City and Society.

Caldeira, Teresa. Worlds Set Apart.

Tailor-made Intervention

Much of the first world views favelas and slums as places devoid of intellectual activity and creativity. It can be difficult for those unfamiliar with life in informal settlements to understand just how much activity, creativity and ingenuity is truly present and encouraged by informality.

When faced with a series of unique, seemingly impossible to solve problems, humans become intensely creative and begin to experiment in order to find the best solutions. While they may appear messy and unorganized to many, they are, in reality, highly organized and planned with a high level of sophistication.

Additionally, when architects get involved in projects in informal settlements with a completely unfamiliar set of problems to be solved, they are also forced to break free from conventional design and planning techniques. The most difficult task that designers and planners have to face in situations of urban renewal and growth is that of instigating social change. Informality is often stigmatized in our society, thus in order truly create positive change, aiding social growth must be at the root of the solution. This is a particular necessity in cities such as São Paulo, where the wealthy live in complete separation from the poor, and barricade themselves into secure, gated communities, in order to completely ignore the reality of their city’s situation (Caldeira 168).

Additionally, there is a necessity for a high level of adaptability and networking in possible architectural interventions in favelas in order to improve the lives of the large percentage of the urban population that is currently being ignored. In order for a design to be successful socially, it must asses and address the local conditions specifically. In Medellín for example, the city implemented a system of cable cars that connects disparate parts of the city, allowing for a greater amount of interaction between the formal and informal (Smith 13). This highly site specific design is adapted to the location and the culture of the favelas in Medellín, thus proving to be extremely successful in comparison to a more generic proposal.

In Rio de Janeiro, the redevelopment and urbanization of the favelas was entirely based on solving the major social issues prevalent in the area. Through the creation of public programs, such as libraries, community centers, and athletic facilities at major transit hubs, the architects hoped to discourage the youth living in the favelas from becoming involved in drug trafficking (Jáuregui 63). The concept of social interventions, while common in certain senses in the first world, takes on a different form when used to revitalize an entire favela. It requires innovative and creative thinking on every scale from small interventions such as adding benches or putting a mural in a public space to massive urban infrastructure projects. By strategically planning out the locations of public buildings in a city, the architects hope to sway an entire youth population towards certain socially beneficial activities. This, in turn would have a drastic effect on the future of the city as a whole. The major question is, will this have a lasting impact on the community, or is it simply idealistic?

Jáuregui, Jorge Mario. Articulating the Broken City and Society.

Smith, Cynthia E. Designing Inclusive Cities.

Caldeira, Teresa. Worlds Set Apart.

Getting Results

With the enormous increase in the population especially in urban areas, we are struggling to find a humane solution to the overcrowded, temporary, and erroneous spaces one third of the worlds population is living in, the slums. Throughout time we have made many attempts at “helping” these people, but it usually ends up destroying their homes, displacing them, forcing them to again, fend for themselves, creating more of a problem than was originally present. But what can professionals do to design for these people, when the shiny skyscraper or clean beautiful city is what we envision ourselves to design.

This is unfortunately what happens a great deal of time, slums are cleared for this expensive great design, in the name of capitalism. This doesn’t have to be though, we can design beautiful things as we want, prove the capitalists wrong, provide a wonderful environment where slum dwellers can create an economy and make money, and help the people live overall better lives. It has been done, and is highlighted in the book Design With The Other 90%: Cities.

Most of the projects outlined in the book are an attempt to provide a framework for success, in other terms giving them a compass or simply pointing them in the right direction, whispering, this is the right way to go. This method provides the framework of the formal, that we believe works, while still providing the means to construct and design the way the people in slums have been accustomed to; piece by piece, typically with found construction materials.

In the chapter Designing Inclusive Cities, Cynthia Smith tells a man she interviewed from the slums that she intended to “find successful design solutions to rapidly expanding informal settlements”, she then goes on to explain that the most promising of these solutions, “were hybrid solutions that bridge the formal and informal city.” (1) Though she claims these are hybrid solutions, I can’t help but understand them as infusing the informal with the formal, rather than a true hybrid, examples of this would be bringing bank loans and social security to those living in the slums of Bangkok (2).

Other solutions such as registering and providing brightly colored and numbered vests to drivers of illegal or unregulated motor-taxis allows the demand to be met for cheap transportation in the slums.(3) This solution seems much more of a hybrid solution than and not simply providing what we deem necessary things like social security and bank loans (thought probably very help for those living in slums).

Participatory planning (similar to the “kit of parts” or “framework” discussed in paragraph three), another great solution to conquering the slum’s problems. In Diadema in Brazil, by the use of these participatory planning methods, its citizens “drew up plans and allocated the resources necessary to drop the murder rate from 140 per 100,000 to only 14 per 100,000 in 10 years. (4)

Another strategic example, not necessarily participatory but one of linkages, was the design for a cable public-transportation system in Medellin, Columbia. This solution allows those living in the poorest neighborhoods to travel safely and gain access to the infrastructure (libraries, business centers, schools, medical facilities, etc. provided in the more wealthy areas of town. (5) This holistic linkage solution allows the city to be incorporated into one united body rather than the slums acting as a parasite to the wealthier portions of town.

These examples attempt to incorporate the slums rather than shun them which is typically the case.The infrastructure most of us take for granted that provides us with knowledge and stability are finally being provided to those who are hard-working but destitute.

1) Cynthia Smith. (Designing Inclusive Cities), Design with the Other 90%: Cities. P. 13.

2) Cynthia Smith. (Designing Inclusive Cities), Design with the Other 90%: Cities. P. 13.

3) Cynthia Smith. (Designing Inclusive Cities), Design with the Other 90%: Cities. P. 13.

4) Cynthia Smith. (Designing Inclusive Cities), Design with the Other 90%: Cities. P. 16.

5) Cynthia Smith. (Designing Inclusive Cities), Design with the Other 90%: Cities. P. 16.

The Imported City

In “Generic City, S,M,L,XL” Rem Koolhaas asks, “Did the Generic City start in America? Is it so profoundly unoriginal that it can only be imported?”(2.2). It seems that the shift of movement out of the city rather than in has caused an emotionless calm of character making these cities generic. The global market has not only looked at foreign models for business capital, but also for their urbanism. In the efforts to become capitalist, higher classes are moving to the suburbs into gated communities designed off foreign models making the city loose its identity and culture.

The city must have place and without place, the character and identity are lost. The Generic City is made by populations/cultures on the move.

“The same (let’s say ten-mile) stretch yields a vast number of utterly different experiences: it can last five minutes or forty; it can be shared with almost nobody, or with the entire population; it can yield the absolute pleasure of pure, unadulterated speed-at which point the sensation of the Generic City may even become intense or at least acquire density…” (3.2)

Without the controlled experience which occurs in a city, there is no memory. The identity is constantly changing. It becomes gray within a black and white picture and everything blends and blurs together. There are no clear connections with other parts of the city or with other people and cultures. Without culture, the Generic City gets imported through the global market blurring the lines of large geographical and cultural boundaries.

Capitalists and the global economy have been pushing the generic city while also destroying the city which once had identity. As seen in Beijing, capitalists and the government have been destroying, abusing, and suffocating money from the poor. These efforts are not only for economic value, but also for the rich to move out to the suburbs. They have imported cities like the Chateau Maison-Laffitte which was a copy of the one designed by Francois Mansart in 1650. There is a direct insertion into a culture which cannot appropriately benefit. What was once a village with farmers and cultivation and a lot of culture and history, is not a Disneyland effect of capitalism. As these different cultures get inserted on a global scale, there is no chance to return back to identity. The world is becoming an unclear, gray, super-society.

Koolhaas, Rem, and Bruce Mau. S M L XL: OMA. S.l.: S.n., 1993.

Broudehoux, Anne-Marie. Delirious Beijing: Euphoria and Despair in the Olympic Metropolis.