In their book Empire, Hardt and Negri offer a fresh understanding of the proletariat, “as a broad category that includes all those whose labor is directly or indirectly exploited by and subjected to capitalist norms of production and reproduction,” (Hardt and Negri 52). This understanding is important to keep in mind when considering the population of over one billion living in informal communities operating in globalized capitalism. While some suggest that many of the jobs that make up the informal community are entrepreneurial in nature, limited access to resources and capital render these “entrepreneurs” as proletarians involved with the exchange of the scraps of bourgeois productive forces.

Mike Davis correctly notes that the explosion of informal settlemtns is part of a semi-proletarianization process that continues in the tradition of 19th century Naples (Davis 174). Instead of reflecting an explosion of micro-capitalism, the trend represents the inadequacy of non-urban economic forms in the rush of 21st century capitalism. Informal settlements become hyper-saturated markets for the consumption of developed capitalism’s waste and contrived levels of unemployment. Just as the unemployed masses of the 19th century were a byproduct of capitalism itself, informal communities and the informal economies that sustain them are not accidents of postindustrial capitalism. Rather, they serve to continue the expansion of capital relatively. The mangnitude of unemployment cheapened the cost of labor because any efforts at collective bargaining could be made null by the rapid replacement of an organized workforce with scores of unemployed masses.

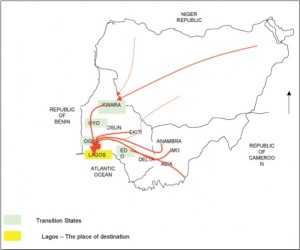

In a similar trick of the market, the electronics market in Lagos (perhaps the most efficient and highprofile example) recycles the detritus and obsolescence of capitalism by exploiting previously-excluded markets (Koolhaas 702). Antiquated electronics of the late 20th century become the epitome of 21st century technology for a market that is constantly expanding in a strikingly dense manner.

Beyond the more “formal,” informal political structures described in the report on Lagos, the development of informal settlements on the scale witnessed thus far suggests that there is the potential for a new political/spatial logic that exists outside of capitalist globalization. If Haussmanization processess in the 19th century brought urban space under the control of the bourgeois state, the scope of informal settlements in the 21st century generate possibilities of extra-state resistance and alternative forms of social organization. Neuwirth, in contrast to Mike Davis, commented on conditions in informal settlements somewhat positively. Some residents remarked that the communities within informal settlements often allowed for a sense of freedom and human solidarity that were otherwise unavaiable in the formal city (Neuwirth 5). Beyond this sense of community, one can speculate the ability to radically critique the global capitalist system. Without fetishizing underdevelopment or caricaturing “the natives’ creativity,” informal settlements are sites of constant growth, dynamic change and close contact between previously-unrelated masses of people. The potential for this in shaping consciousness in gigantic; modern processes of urbanization are transforming into processes of hyperurbanization without similar levels of economic advancement. In this sense, the new expanded proletariat is becoming a global phenomenon far surpassing the industrial proletariat of Marx’s days.

Bibliography

Davis, Mike. Planet of Slums. London: Verso, 2006.

Hardt, Michael, and Antonio Negri. Empire. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 2000.

Koolhaas, Rem. Lagos: How It Works. Baden: Lars Müller, 2007.

Neuwirth, Robert. Shadow Cities: A Billion Squatters, a New Urban World. New York: Routledge, 2005.