Micro-Finance or Micro-Reaction?

While micro-finance has proved successful in lifting families out of poverty it is politically problematic for two major reasons: it perpetuates capitalist social relations, thereby masking the root cause of poverty and the system is susceptible to manipulation by larger financial entities which charge interest and run counter to the socially conscious vision of Muhammed Yunus.

Yunus’ vision, while admirable, ultimately falls short because in the end it relies on a belief in “capitalism with a human face.” His vision asserts that the periodic crises in global capitalism are the result of greed and mismanagement as opposed to a systemic problem. The system of micro-finance that he pioneered gives people the impression that global poverty can be significantly reduced by small actions and that even the most basic economic exchanges should be formalized in the capitalist market. Furthermore, the valid sense of hope generated through his model’s successes potentially negate any hope for concerted political action that would demand jobs and services (such as healthcare) that should be treated as rights in the first place. The ideological implications of belief in such a system may outweigh the on-the-ground benefits in the long run.

Poverty is not accidental and such assertions that globalization can be transformed to include the Global South as a beneficiary are naïve at best. The systemic issues of global capitalism and its symptoms of hunger and poverty cannot be adequately addressed through micro-finance. The international working class is thoroughly productive and yet poverty and chronic unemployment are a result of mismanaged distribution at the hands of the owning class.

While it is obviously good to lift families out of poverty, and micro-finance has proven successful in many instances, the political implications of such a reliance may in fact maintain extreme levels of income inequality and power across the world. If the solution were as easy as giving every poor family a small sum of money, global poverty would have been history years ago. The system of micro-finance enshrines bourgeois social relations and provides a false sense of hope for the class that in reality produces the world’s wealth through its labor.

1. Dr Toh Han Chong, Interview with Professor Muhammad Yunus, SMA News, Volume 40 No. 12 December 2008.

Microcredit across disciplines

The microcredit system, with all its success around the world, is an impressive solution to the lack of opportunity that keeps the poorest of the poor from climbing out of poverty. Using funds that are relatively small sums to encourage investment and the building of enterprise, with a system of trust for repayment, has the potential to eliminate poverty from society, as Professor Yunus describes[1].

When thinking ahead, what happens if/when the microcredit system becomes so successful that many of the poor households using the system are now off and running with their own enterprise or investments? One of the conditions of the microcredit system was that loans would not be used to purchase food or clothing, etc.

Another scenario that may have an interesting result is the use of microcredit across disciplines. Professor Yunus discusses how his healthcare ideas have used the system to help with one of the most demanding needs of life, and how it functions on the basis of trust when medical care must be given without payment being available up front. However, there are many other services and fields that provide necessities for those rising out of poverty. Architecture, for example, and the construction industry can provide the necessity of shelter, as well as arrangements for incorporating other family members or tenants into a living situation. Would microcredit also work for services such as architecture? Or would those services be considered enterprise for an investment?

Another idea is the concept of bartering; Professor Yunus’ interviewer discusses how Bangladesh is a homogenous culture of religion and people, with similar understandings and traditions and worldviews. If microcredit can work as a system that improves the culture and people group as a whole, instead of one person here and there, could bartering be used as a means of “income”? This could function on a larger scale than trading bread for a scarf for example. If a few people can wire electricity to your home, or provide construction labor for a new home, you could potentially repay them with another service they require. This is less applicable the more formal a society becomes, but may have potential to offset the lack of opportunities related to monetary income, and could potentially be organized in a record-keeping type manner, such as the microcredit loan system. Food for thought perhaps!

1. Dr Toh Han Chong, Interview with Professor Muhammad Yunus, SMA News, Volume 40 No. 12 December 2008.

Social Investment

When dealing the crisis of poverty, most organizations and governments follow the prototype of social expanse on low-income families. However in the free market in capitalism system, it is hard and takes more effort for these “charities” to survive with more expanse than income. As Yunus mentioned in the interview “a market must be developed as a self-correcting system”, social conscience practices need work as a sustainable system that generate profit in the process of helping the poor and keep the organization survive independently. Both Grameen’s microcredit system and Elemental’s practices are based on the philosophy of creating wealth and helping the poor at the same time.

It is Yunus and Aravena’s trust on the ability and the contribution of local dwellers and the poor that makes their practices so successful. When talking about the inspiration of his belief in social enterprise, Yunus thinks that it the village women who “struggle daily for dignity and to create a good life for themselves and their families” (Dr Toh Han Chong, 5). The creativity and hardworking of the poor give passion for these social enterprise to invest and provide opportunity for poor people. Yunus believes that the reason for poverty is the lack of opportunity.

In order to help the poor, Grameen microcredit bank provides the low-income family with the opportunity to generate more income. And the regulating system with their outreach workers can make sure that the borrowers are using the loan for income generating purposes so that they will have ability to pay back to Grameen bank and have more money to support their families. Yunus extends this idea also to the Grameen Healthcare (GH) that they provide healthcare service first and the poor patients can pay for the service sometime in the future.

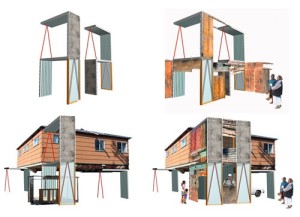

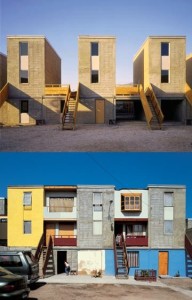

Aravena and Elemental uses similar philosophy in their architectural practices. The completion of buildings is not only architects’ job but also based on the dwellers themselves. Elemental provides highly designed architectural framework and leave the space for local dweller to add or change the building depending on their needs. Social enterprises like Elemental “empower local builders by giving them the knowledge that allows them to take these same innovations and apply them themselves” (Aravena, 35). This kind of practices saves the time and cost that are the most important in social housing projects. Each owner builds the second half the house and is responsible for “customizing the final solution” (Aravena, 35) in Elemental’s first practice in Iquique project in 2003. The value of houses increases because of the contribution of dwellers.

Also, the cooperation between institutions, enterprises and governments makes social investment easier in practice. “This unusual combination of academic excellence, corporate vision and entrepreneurship has been instrumental in enabling Elemental to expand its scope in the city” (Aravena, 32). Similar to Grameen, they create a health network that combine university and hospital center “hub” including a nursing college to serve for clients.

The sustainability should be the focus for more social organization and enterprises. Aravena and Yunus’s success give us good examples of social investment rather than only social expanse in social practices.

1. Dr Toh Han Chong, Interview with Professor Muhammad Yunus, SMA News, Volume 40 No. 12 December 2008.

2. Alejandro Aravena, ‘Elemental: A Do Tank”, Havard Design Magazine 21, Fall/Winter 2004/5.

Beyond Charity

Traditionally the poor of the world have not had access to banking as they are deemed not credit worthy. This presents a problem as one cannot make money without having any in the first place especially in areas where jobs are scarce. Those who have no choice but to take out a loan are forced to use loan sharks who charge exorbitant interest rates which most cannot repay, thus enslaving and sending those who took out the loan further into poverty.

A viable alternative to loan sharking and traditional banking is what is called microcredit. The idea of this loan system is to give small amounts of money to groups of people in need. This group based credit approach ensures loans are repaid due to the peer-pressure of the group. The idea of this system originally came about when Professor Muhammad Yunus was teaching economics at Chittagong University in Bangladesh. He felt useless teaching those who could barely afford to eat economics in the classroom, therefore he set off into the streets of Dhaka to see how he could be instead helpful. While conversing with those in the street he found that many people were enslaved to loan sharks, of those he talked to, 42 people were unable to get out of this situation. He decided to give them the money to free themselves and as soon as they were able to do so, they repaid Yunus.(1) This anecdote is the foundation for Grameen Bank.

The goal of Grameen Bank, founded by Professor Muhammad Yunus, is to break the cycle of poor generation after generation by allowing the them to borrow small amounts of money to invest in either a business or agriculture. This process is called microcredit and as Muhammad Yunus states it “is intended to help poor people work their way out of poverty.” (1) In contrast to Grameen bank, the traditional banking system and loan sharks, only push those in poverty further down. These business models are focused on making a profit rather than aiding those in need. The interest earned by Grameen bank as opposed to typical banks is that it only uses interest to allow new loans to occur so that other members of the community are aided. Grameen bank focuses on elevating the poor and the community as a whole by allowing them through their loans a means to lift themselves out of poverty.

Throughout time the microcredit method has helped many poor families in Bangladesh and has since been transferred to other poor areas of the world. In addition to this expansion, the idea of microcredit has also been re-imagined as a means of aiding those who find themselves unable to afford healthcare or in situations of natural disasters. During times of natural disaster Grameen Bank dedicates itself to the welfare of its members by acting as a humanitarian organization to those affected.(1) On the healthcare front, Grameen Healthcare was founded upon the same principles as Grameen Bank. At Grameen healthcare no one will be turned away from receiving the care that they need. Payment is negotiable and can be done when you have the ability to do so, taking the stress out of healthcare.(1)

The ideas established by Professor Muhammad Yunus understands the necessity of the poor to get loans and repay, not by fear but by trust. The idea of microcredit allows those who take out loans the ability to get the money they need without much stress and in addition keeping their dignity in the process. This allows those getting loans the ability to elevate themselves by their own talents.

(1) SMA News: Interview with Professor Muhammad Yunus: Edited by: Dr. Toh Han Chong

Bridging Economics and Social Practices

Economics as Professor Muhammad Yunus has implemented it has truly bridged a path between its typical competitive capitalist association and its philanthropic capabilities. It is through this bridging process that he has learned not only the importance of his work but also different ways that others can contribute to this new initiative to solve poverty.

It was through his observations of corrupt loan practices in Dhaka, Bangladesh that he was first inspired to utilize his profession as a form of activism to solving social economic problems. Furthermore, it was through observation that it was learned how to better implement his newly created and more honest practices of providing loans. For example, it was through practice and observation that Prof. Yunus found out that his loaned money would better benefit families, as he states, “Over time we noticed something interesting. The loans that went through the women appeared to have a greater development impact on the family.” [1] This discovery would be then applied to other microcredit programs around the world.

Professor Yunus’ utilization of his loan program serves as a bridge connecting capitalism as it exists today and social business. Accommodating social businesses into capitalism allows for a “solution of many of the problems we see today.” [1] The goal of these social driven businesses are to provide assistance to many of the social and economic needs of citizens in less than favorable situations. Many of these issues deal with malnutrition, safe drinking water for rural areas, and other. In essence there needs to be a balance between the output that capitalism provides and better connecting it with entrepreneurial work. It should not be that one is limited to help society through charities of non-profit organizations because these sometimes limit the amount of work that can be done and are very specific to their utilization while private companies for example can provide more fluctuation in the way money is utilized.

Many government programs across other countries have begun to utilize this bridging method such as the Compartamos program in Mexico. However, many of these programs continue to keep interest high and as a result turn out to be the same form of corrupt money lending strategies that inspired Yunus many years ago. The goal as result needs to be clear and it needs to specify that the objective is to bring people out of poverty and help them develop a good economic standing from where they can increase their chances of socio-economic mobility.

Through these initiatives Prof. Yunus hopes to eliminate desperate practices such as those of organ trade that can really affect the mental and physical health of poor communities in Bangladesh. Of course he understands its way of providing for those in dire need and instead discourages its banishment but rather encourages its regulation. While loaning is effective one must consider the needs of families that receive these loans. Through, once again, observation it was found that most families spend quite a bit on health care and as a result don’t amount to much economic recuperation. As a result many of his economic initiatives are attached to healthcare related ones. As Yunus states,” our vision is to deliver radically affordable, sustainable and world class quality healthcare for all.

If many more professionals dedicated a portion of their fields to create a bridge between their profession and philanthropy and social funding the state of this world would change. Many times we find ourselves enveloped in our own professional world and lose sight of what surrounds us but if we utilize the passion that we have for our profession and find a way to balance it then a new more desirable world can be produced. This of course has to come from our own initiatives because this change has to come from one’s own desires and not from anyone else.

1. Dr Toh Han Chong, Interview with Professor Muhammad Yunus, SMA News, Volume 40 No. 12 December 2008

Readapt the Habitat

Architecture Creating Opportunities

Professor Muhammad Yunus said in his interview in the SMA News that “if we can just provide the opportunity to poor people, there is no reason for poverty to remain a part of our societies” (Chong 5). While Professor Yunus was speaking in terms of microlending in this case, why is this particular concept not extended to architecture? He mentions that by bringing social businesses, which are “non-loss, non-dividend companies designed to address a social goal,” into the marketplace, we can improve the lives of the poor (Chong 4). Architecture firms could easily fall into this category, since they are still for-profit organizations for the most part, but have the ability to make drastic changes in peoples’ lives.

The work of Alejandro Aravena with his firm Elemental, for example provides housing to those who are desperately in need, yet it is still a for-profit organization. How can a firm balance their own need for profit with the desire to help others? A combination of micro lending and government funding may be a viable answer. When developing large scale projects like Iquique Housing in Chile, using micro lending in addition to government funding would increase the project budget, as well as provide a greater sense of ownership for those who will live in the houses. By taking out a loan in order to improve their house, they will immediately have a connection to it and care about its appearance, maintenance, etc. This will improve a home’s lifetime and, using Iquique as a model, the price of the home can increase exponentially in a short span of time (Aravena 32).

As we have seen throughout our investigations of architectural interventions in poor areas, participation is a key factor in a project’s success. Increased input from the community allows for final products that reflect the needs of the users, resulting in an increased interest in the project’s future. When people have put time, effort, and money into something, they are far more likely to care for it going forward. In this way, micro lending will drive those in impoverished areas to truly care about their surroundings in a new, positive way.

Providing those living in informal settlements with a stake in their homes and communities will provide them with an opportunity to get out of poverty. There is an opportunity for economic improvement through increasing property values as well as through the income from the shops that often take over the ground floor of homes in settlements such as Iquique and PREVI. Micro lending in conjunction with any available government funding is a clear and simple way to raise money for projects, increase community participation in the design and construction, as well as improve the lives of the poor going forward by giving them a home that over time can be profitable to them. It will allow architecture firms to remain for-profit companies while still aiding those in the most desperate need of their services.

Chong, Toh Han. “Interview with Professor Muhammad Yunus, Founder of Grameen Bank.” SMA News 40.12 (2008): 2-7

Aravena, Alejandro. Elemental: A Do Tank

Spatial Subversion and Political Opposition

Any spatial challenge to the inefficiencies and inequities generated by the global domination of capital requires a principled political opposition and the social engagement of the most oppressed sectors of the working class. Spatial agency and networking are important tools to realize the goals of an anti-capitalist movement. While Lenin speculated on the subversion of bourgeois state power through the creation of a dual state, there is a more immediate potential for the generation of subversive spaces that have the ability to serve as a nucleus for further revolutionary action. Squatting settlements and slums are two examples where space functionally exists outside of state power.

Beyond some romantic revival of youthful 60s-inspired rebellion, these spaces can have explosive political consequences. The FARC-EP, though primarily based in Colombia’s countryside, operate urban networks of alternate governance in the informal neighborhoods of Colombia’s largest cities. This shadow government owes its efficacy to the informality of the space itself. While this example is certainly extreme and related to a specific political/geographic context, it demonstrates that informal conditions can generate highly sophisticated forms of spatial and social organization. Namely, the working class is capable of generating its own culture and spatial livelihood under even the worst circumstances.

The next step in reorganizing space, drawing from Teddy Cruz’s methodology in Tijuana, is from the design point of view. The organization of the building project itself along a community-oriented mentality is capable of transforming how communities think about space. Teddy Cruz does not merely propose recycling San Diego’s capitalist refuse to build individual housing units; he contends that the act of social organization necessary for such an endeavor will reinvigorate a larger sense of collective power. Finally, he recognizes that the state will only recognize new settlements with infrastructural improvements only when these settlements exist as at least semi-permanent communities.

However, Cruz’s approach highlights the political roadblock that even the most well-intentioned projects encounter: how does one reconcile a principled critique of unjust systems while working to improve the lives of those most adversely affected by these systems? Cruz’s speculative design for housing in Tijuana has many positive, potentially liberating elements but does it not also ignore the glaring contradiction that Mexican labor is hyper-exploited by the Mexican and American bourgeoisies, literally bound by a wall to prevent any chance of social mobility and then forced to consume the leftovers of U.S. capitalism’s overproduction (in this case physical refuse and under-valued capital in the form of housing)? Architects must not only creatively work in contradictory, oppressive political climates but join movements to dismantle them.

Aquilino, Marie Jeannine. Beyond Shelter: Architecture and Human Dignity. New York, NY: Metropolis, 2010.

Awan, Nishat, Tatjana Schneider, and Jeremy Till. Spatial Agency: Other Ways of Doing Architecture. Abingdon, Oxon [England: Routledge, 2011.

Cruz, Teddy. Tijuana Case Study: Tactcis of Invasion: Manufactured Sites.

Role of architects in informality

In the final section of the book Spatial Agency, the author discusses how spatial agents operate the concept inherent in these operations of the groups and practices.

It leads to the rethinking about the role of architects, especially in practices related to informal condition. Architecture can no longer be a beautified and technologized object and solve all problems alone. Especially when the book introduces spatial “appropriation”, architects need to face the fact of squatting and illegal self-building practices, in which new activities are created and embedded with long-term opportunities. The production and knowledge of clients and other forces is relatively more important compared to that in formal projects and should be included in the process of construction. The mark of architecture project’s completion has to be extended in order to consider the use of clients (informal recreate). However, the book also points out that today too often over-determined projects lead to inefficiency of space, as over-determined space is hard to transfer for other usage. While, some “slack” space, considered as wasteful and uneconomical, provides delight indeterminacy for everyday ordinary needs of transformation of space. Architects’ job is to set up the framework of a project with their professional knowledge and leave space for the inhabitation. In Teddy Cruz’s description about his practices in San Diego and Tijuana’s borderline, he invents a frame that cooperates with recycled materials and other human resource to “help dwellers optimize the threading of certain popular elements, such as pallet racks and recycled joists” as well as “acts as a formwork, allowing the user to experiment with different materials and finishes.” (Cruz, 35) Plus, the stair system benefited from this frame intervention accelerates the receiving of recycled houses from San Diego. The scale of architect’s part in this practice is relatively small, which is just simple transformable frame. However, the scale of this project is expanded incredibly big through the process of using these frames by residence with collective force. The indeterminacy is the basis for more future possibilities of the projects.

Based on the understanding of limitation of architecture and architects’ skill, we should agree with Marcuse’s view of using our skills in coalition with other groups to solve issues of capitalism in complex urban informality. In the book, author believes that “spatial agency is driven by the managing and administration of means such as labor, time and space.” Architects, as one important role with professional knowledge in the spatial agency, should take the initiation to collaborate with all other forces and spend time negotiating in order to make up the limitation in our knowledge and ability when facing such complex systems. When talking about “sharing knowledge”, the book says “architecture was not about supposedly neutral form, but about the collaboration with others in an attempt to make architecture and architectural tools more relevant to a broader section of society.” (Spatial agency, 78) In Teddy Cruz’s project in Tijuana, distribution of goods, ad-hoc services and the whole material recycling system connecting Tijuana and San Diego are all important aspects that architects need to negotiate and take into consideration in addition to the design.

1. Spatial Agency

2.Teddy Cruz, Tijuana Case Study